See a related article from the Ecology Center's website, Toxic at Any Speed: Healthy Cars

Clean Car Campaign

The Ecology Center launched the Clean Car campaign amidst growing evidence that interaction with everyday items, like cars, could be dangerous. Some of this came from evidence after a 1989 law requiring children on Medicaid be tested for lead. This national law recognized that children on Medicaid were most likely to be exposed to lead poisoning because children living in poverty are more likely to live near plants that spew dangerous chemicals. This is by design - a partial result of discriminatory housing practices and voter disenfranchisement.

Still, while Medicaid paid for 100 percent of testing and treatment for children, it did not pay to test the source of poisoning, including macro-environmental factors, like factory pollution, and micro-environmental factors, like paint, car interiors, and pipes. Lead is particularly toxic to children and their developing nervous system, impacting growth, motor coordination, learning capabilities, and cardiovascular health, to name only several impacts.

The Ecology Center recognized that children living in poverty and disenfranchisement were most likely to be impacted because of the above risk factors, because adults in their homes could not afford to test the source of infection given the lack of Medicaid support, and because factories and sources of toxic spew settle predominantly in poor, African American neighborhoods - by 1997, the city of Romulus, a predominantly working class city that houses DTW, had one toxic waste facility for every 140 residents.

The Ecology Center’s Clean Car Campaign kicked off in the summer of 1999 with a belief that “Clean Cars” presented a pathway to tackle broader problems that happen in the process of incinerating vehicles. For more on this, see the story about municipal incinerators. Partnering with organizations like Great Lakes United and the Union of Concerned Scientists, the Ecology Center launched a website to collect clean car pledges and post important information. The EC also engaged with members of the auto industry because, “a key goal of the campaign is to promote the purchase of vehicles auto makers say they would like to produce.”

Around the same time, General Motors decided to ban PVC from car interiors. PVC is a plastic that, when incinerated, releases dioxin into the atmosphere, which settles into the soil and groundwater. While the Ecology Center heralded this decision, it is important to understand that GM eliminated the plastic due to its lack of durability rather than for environmental purposes. GM also planned to continue using PVC in other parts of their vehicles. This victory, though symbolic, did pave the way for more discussion and action around dangerous substances in something so ubiquitous as car interiors. As stated by Alexandra McPherson in From the Ground Up:

“GM's decision addresses two components of the Clean Car Campaign’s clean manufacturing standard: Elimination of substances of concern, and design for recyclability and maximum use of recycled materials.”

Like lead - found in, among other parts, wheel weights - and PVC, the Ecology Center also identified mercury as a dangerous toxin commonly found in cars. When inhaled, mercury vapors can cause neurological and behavioral disorders like tremors, insomnia, memory loss, muscle weakness, neuromuscular changes, and headaches. Mercury can also create other preoblems related to the kidneys and thyroid. The Ecology Center in partnership with Environmental Defense, formed Partnership for Mercury-Free Vehicles (PMFV) to promote automaker responsibility, with an ultimate goal of establishing a national auto switch recovery program.

Car manufacturers used mercury in switches for vehicle hood and trunk convenience lighting. While the state banned the use of mercury in common objects like thermometers in January of 2002 (though the legislation would not take effect until January 1, 2003), mercury remained relatively commonplace in cars, particularly cars manufactured in the 1980’s and 1990's.

On December 19, 2002, the Michigan State government released the Michigan Mercury Switch Study. The study found that removal during initial vehicle processing took about half the time of recyclers conducting yard sweeps. The EC issued a press release about a three-month long study that MDEQ had just completed regarding the recovery of automotive switches containing mercury from “end-of-life” vehicles. The study confirmed that nearly 2.7 million vehicles on Michigan’s roads contained mercury, equaling nearly 5,000 pounds of mercury. Up to 5% of switches were significantly corroded, meaning that passengers in such cars ingested mercury. The study found an average .54 switches per vehicle, a number that would have been even higher if it included a more representative sample of older vehicles, which generally have more switches per vehicle.

On January 30, 2002, the Ecology Center, in partnership with the New England Zero Mercury Campaign, released a new report that showed that mercury-containing cars were most often disposed of through incineration, leaching an estimated 239 pounds of mercury per year into the atmosphere, soil, and groundwater. This devastating finding revealed that mercury switches ultimately contaminate fish, directly impacting Michiganders’ food supplies.

As part of the PMFV, a national coalition, representatives from the Ecology Center traveled to Maine to voice support at the Maine State House for legislation aimed at removing mercury-added components from automobiles. The Maine legislature ultimately passed “the nation’s first law to mandate manufacturer responsibility for the removal of toxic mercury from vehicles” on April 4, 2002. The law required automakers to establish a system for safely removing and disposing of the mercury used in cars and trucks.

Yet, the fight was not over in Maine, after automakers challenged the mercury switch law, a result that could have spelled disaster for the fight against mercury switches across the country, as states like Michigan modeled legislation after Maine’s test case. Fortunately, the US District Court upheld the law, which requires automakers to pay to recover toxic mercury found in cars and pay a $1 bounty to unkyards for mercury recoveries. This is important because it discourages continued use of mercury switches in new cars.

That same year, the Ecology Center helped pass a landmark law that shifted responsibility for switch removal to automakers, a bill that marked a great leap forward in PMFV’s founding goals. After much anticipation, the Michigan Mercury Switch/Sweem (M2S2) Program began in August 2004. The Michigan DEQ and the Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers entered a memorandum of understanding, with a goal to remove mercury switches from 80 percent of all end-of-life vehicles processed in Michigan. In the first year of the program, M2S2 collected 8,000 switches.

In November 2003, the Ecology Center returned to lead. Its “Automotive Lead Safer Substitutes Project” dubbed the need for “Lead Free Wheels”. Wheel weights are corrective, helping balance the wheels. Lead was a convenient material for this purpose. Wheel weights can litter highways and make their way into waterways and travel through the air. Most commonly, however, like mercury, lead is released into the atmosphere when cars are incinerated.

By 2004, Mercury reached new high levels. The Ecology Center released a report that found mercury pollution levels rose to a staggering 18,000lbs in April 2004. This finding spurred new action on the state level.

In August of 2006, the automotive manufacturers created the End of Life Solutions Corporation (ELVS). This service provides resources and free services to yards and dismantlers to enable the efficient reduction of mercury incineration.

The recovery plan works by easing the burden of recovery on junkyards. Participating yards remove mercury switches from vehicles at end of life and put them in containers provided by the National Vehicle Mercury Switch Removal Program. Then, they ship the containers, prepaid, to EPA-approved warehouses, which then ship the pellets to approved mercury recyclers.

The Ecology Center called this an important first step to ensuring that mercury does not end up in soil and groundwater. But Jeff Gearhart, the Ecology Center’s Auto Project Campaign Director at the time, said that the program will ultimately either be over-burdened or unable to manage every mercury-containing vehicle. Gearhart estimated that 4.5 million switches were set to be recycled in 2007 alone, but the official goal of the program was only 4 million over the course of its first three years.

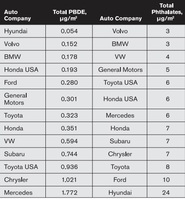

Given the precedent set by the unsuccessful challenge to Maine’s mercury switch recovery law, the Clean Car Campaign escalated its goals, seeking to eliminate more toxins from cars, which spread to live on in soil and dust. The EC singled out phthalates, which were used to make plastics more flexible and harder to break, replacing PVC - it’s important to remember here that GM eliminated PVC from interiors seeking a more durable, not necessarily environmentally friendly, alternative. The EC was also particularly concerned with a PBDEs, a class organobromine compounds that are typically used as flame retardants. Both chemicals are toxic, and both were commonly found in cars. Chart of toxins in cars. This battle escalated when, in 2008, the Ecology Center conducted a study that found large amounts of PBDEs behind car windshields.

The Ecology Center continued its fight against mercury poisoning when, in August, 2009, General Motors claimed that it was not responsible for funding recovery and recycling of mercury switches from old vehicles. A coalition of environmental groups, which included the Ecology Center, expressed concern and dismay. Charles Griffith, the Ecology Center Clean Car Campaign Director said:

“GM should not be hiding behind a bankruptcy proceeding as an excuse for not meeting its on-going obligation to fund a vital program for keeping mercury out of the environment.”

According to industry estimates, 54% of all vehicles containing mercury were GM models at the time. The Ecology Center believed that, because GM represented over half the impacted vehicles, GM was responsible for funding half the costs of the industry collection program, nationally.

The program lacked financing in part due to the Great Recession, a crisis that GM hoped would exonerate it of financial responsibility. Environmental groups argued that GM’s lack of financial support “detracts further from an overall lack of financing necessary for the national program to operate effectively.” A month prior, in July 2009, a separate fund that gave financial incentives to auto dismantlers for turning in switches ran out of cash. In short, the Great Recession almost spelled the end of this critical national program.

The fight against lead wheel weights gained momentum in 2009 when the EPA reversed a 2005 decision, accepting a petition from a dozen environmental and health organizations, including the Ecology Center, to immediately begin rulemaking to ban lead wheel balancing weights. Lead wheel weights (which are used to balance vehicle tires so that they don’t vibrate as they spin) represents “one of the largest unregulated uses of lead in consumer products today.” Jeff Gearhart, the Ecology Center Research Director at the time, said:

"1.6 million pounds of lead from wheel weights is left falling off of cars each year where anyone can find and possibly ingest it. Banning lead wheel weights will greatly protect kids from lead poisoning."

In 2009, there was an estimated 12.5 million lbs of lead left uncontrolled in the environment. On April 28, 2009, Washington became the first state to ban lead wheel weights, recognizing the danger of these items.

In the midst of the recession and into the next decade, the Ecology Center continued its advocacy and coalition efforts to make cars safer for everyone. Propelled in part by testing rules from 1989, the Clean Car Campaign was based on a foundational belief that access to information makes people safer. The campaign was part of broader Ecology Center efforts to make ubiquitous items healthier, or at minimum not toxic.