Community Food Systems

In 2014, Detroiter and retired machinist Bernard Juozapaitis told the Ecology Center that he had “pretty much given up on health issues” until his niece recommended him to the Fresh Prescription program at Community Health and the Social Services (CHASS) Center in Detroit’s Mexicantown. Launched in 2013 by the Ecology Center, Eastern Market, and the Fair Food Network, Fresh Prescription was created to bring together doctors, patients, food-health clinicians, and farmers market vendors to promote and provide Detroiters access to healthier food options. Juozapaitis was a prime candidate for the program. He had long suffered from several undertreated health problems, including diabetes, high cholesterol, and a shoulder injury from his days working as a machinist. Just four months into the program, Juozapaitis’, who admittedly was never much of a “fruit and vegetable man,'' said he was enjoying eating foods he never thought he would have eaten before. With his new diet and exercise routines, Juozapaitis lost about 30 pounds and claimed to have even grown an inch or two. He told a reporter from Hour Detroit Magazine, “You wouldn’t be talking to me right now if it weren’t for that one visit.”

While Juozapaitis found success with Fresh Prescription, many Detroiters still struggled to access fresh foods. The same year Juozapaitis ended his first year in the program, the Detroit Food Policy Council (DFPC) conducted a survey which found that 94% of respondents had concerns about accessing healthy food in the city. A lack of access to healthy food can have major health consequences, including obesity, hypertension, and diabetes.

The Ecology Center has long considered access to safe and healthy food a cornerstone of its environmental justice work. A prior section discusses the Ecology Center’s efforts starting in the early 2000s to persuade large institutions like hospitals and school districts to serve healthier and more sustainable foods. Today’s article highlights the Ecology Center’s involvement in community-based food programs like Fresh Prescription that provide Michiganders with direct access to and knowledge about healthy food.

Fighting for Fresh Food in Detroit

When it comes to responding to food insecurity, Detroit has a long and fascinating history. When the Panic of 1893 left thousands of Detroit families hungry, progressive mayor Hazen S. Pingree responded by proposing an urban gardening program where the city’s unemployed would transform vacant lots into fields of potatoes, corn, beans, pumpkins and so on. Pingree’s idea faced fierce criticism from Detroit’s wealthier classes and from the press, but the program turned out to be an unequivocal success. Over 3,000 families applied to farm lots in 1894. Within twenty years, cities as far away as Berlin began trying their own versions of “Pingree Patches.” When the city was reeling from deindustrialization and depopulation in the 1970s, mayor Coleman Young sponsored a similar urban farming initiative, affectionately labeled “Farm-a-lot.” By the end of the decade, nearly 7,000 Detroit residents were taking part in the urban farming project. When the program formally ended in the early 1980s, organizations like the Gardening Angels, the Detroit Agricultural Network, Keep Growing Detroit, and the Detroit Black Community Food Security Network (DBCFSN) continued the city’s legacy of community gardening. DBCFSN currently operates D-Town Farm, the largest of Detroit’s urban farms.

Urban gardens and farms are just one piece of Detroit’s complex food system, which also includes farmers markets, grocery stores, restaurants, food cooperatives and corner stores. A growing number of corner stores, in fact, are participating in efforts to add more healthful foods to the traditionally unhealthy snack aisles. And, along with D-Town Farm, DBCFSN is in the process of opening the city’s first food co-op that will serve predominantly Black and low-income Detroiters. Several other non-profit organizations have also played important roles in expanding access to food in Detroit, including the Fair Food Network, the Community Health and Social Services (CHASS) Center, and, perhaps surprisingly to some, the Ecology Center.

Detroit Gets a Fresh Prescription

Before starting Fresh Prescription, the Ecology Center had long been involved in healthy food awareness campaigns, ranging from organic gardening projects in the 1970s, such as Project Grow, to pesticides education in the 1990s, to the Healthy Food in Health Care work in the early 2000s. It wasn’t until the launch of Fresh Prescription in 2013 that the Ecology Center got directly involved in community food programs in Detroit. The program was led by Dr. Kathryn Savoie who was hired by the Ecology Center in 2012. Savoie, through her many years of community organizing, had already developed strong relations with Detroit-based clinics like CHASS and American Indian Health and Family Services. These clinic partners would prove to be critical to the success and sustainability of the program.

In designing Fresh Prescription, Savoie and the Ecology Center drew inspiration from existing food prescription models, including Wholesome Wave’s national produce prescription program and Washtenaw County’s 2008 Prescription For Health Program. Although Washtenaw’s program was still relatively new, it served as an important model for the structure of Fresh Prescription.

Here’s how Fresh Prescription works: First, a physician refers a qualified participant to the program, which may include pregnant women, caregivers of young children, and low-income patients who live with chronic diseases. Then, after meeting with a participant and their families, a clinician “prescribes” the goal of eating more fruits and vegetables. Next, participants receive a voucher for $40-$50 (later increased to $90) that they can spend at the CHASS Mercado or other participating farmers markets. Lastly, participants receive ongoing support from clinic staff and have the option of attending nutrition education events.

In its first year, Fresh Prescription reached 48 participants, most of whom reported experiencing food insecurity prior to starting the program. After a year in the program, nearly all participants were consuming more fruit and vegetables than they had before they started the program. Forty-seven participants reported that they had learned something from the program that they would use in the future. With the success of the first cohort, Fresh Prescription opened three new sites, one at the American Indian Health and Family Services (AIHFS) building, one at Joy-Southfield CDC in partnership with Henry Ford Health System, and the other at Mercy Primary Care near Grosse Pointe. The Ecology Center also piloted a food delivery service to aid patients with mobility issues.

The 2015-2016 cohort blossomed to over 300 hundred participants. In that year, an evaluation report conducted by the Curtis Center at the University of Michigan found significant improvements in participants’ access to and knowledge about healthy food as well as changes in their eating behaviors and health. According to the report, “participants’ perceived ability to find the fresh fruits and vegetables in their community rose from 65% at the beginning of the Fresh Prescription program to 80% at the end of the program” (p. 4). Nearly nine out of ten participants reported learning more about the importance of eating healthy foods. Perhaps most importantly, over half the participants went from eating less than one cup of vegetables and one cup of fruit a day to eating between one to three cups. And, nine out of ten participants reported being able to better manage their health conditions.

The Fresh Prescription program also proved to be a boon for local vendors. In the same program evaluation, the vast majority of vendors reported developing new connections with program staff, customers, and other health educators. According to one vendor “One of the biggest strengths [of the program] is that the customer base was very loyal, even though it’s small...It’s not just about being able to buy the produce...it was a weekly hangout spot."

In 2018, the Ecology Center transferred control of the Fresh Prescription over to its community partners, Eastern Market and CHASS, who continue to operate the program. By seeding and then transferring control of initiatives, the Ecology Center has been able to empower regional stakeholders while remaining a small and flexible organization.

When I asked Savoie in 2021 to reflect on what was so significant about Fresh Prescription, she remarked that the program helped “connect the dots for folks in a way that really hadn't been happening.” Patients weren’t just learning about health in the abstract. They were talking with doctors, health providers, and food vendors about food access and how to cook with healthier foods. In doing so, Savoie noted, that you’re not just helping people change their eating behaviors, but you’re also helping to “create a healthier food system...that makes the healthy option an easier option for everybody.” When more people demand healthier food options, the supply of that food increases, benefiting the community and the environment.

Other Community-Focused Food Initiatives

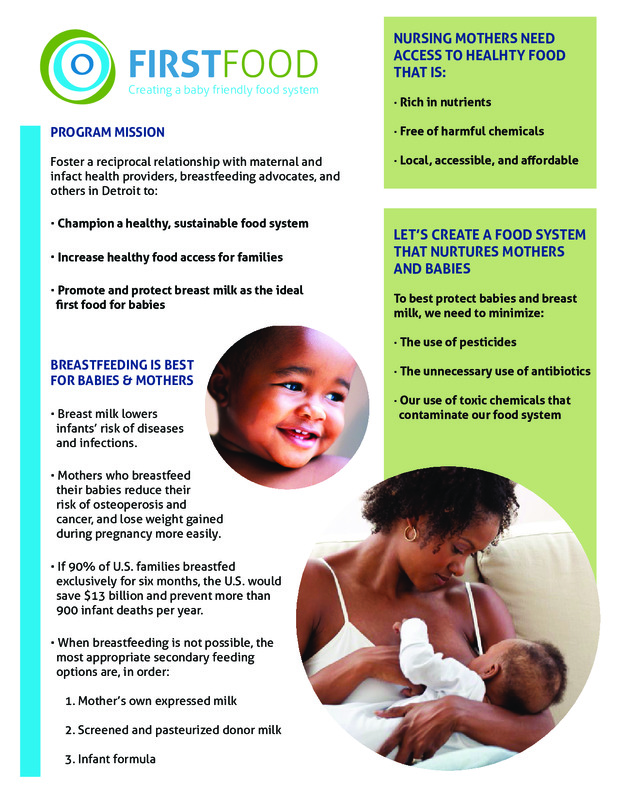

The Ecology Center continued to promote health and healthy eating through additional programs, such as First Food. Funded in part by the Kellogg Foundation, First Food was an educational campaign designed to promote and protect breast milk as the ideal first food for babies and connect young mothers to community food services. To do this work, the Ecology Center worked with the Black Mothers Breastfeeding Association (BMBFA) and the Michigan Breastfeeding Network to produce informational flyers, hold seminars and workshops, and participate in conferences held by BMMFA and the Detroit Food Policy Council. According to Savoie, who led much of this work, one of the Ecology Center’s unique contributions to breastfeeding education was raising awareness about the environmental costs of infant formula and the links between toxins in the environment and breastfeeding. Savoie explained that breastfeeding is a critical part of healthy food systems that’s not often discussed. By leveraging the Ecology Center’s existing food systems programming and resources, First Food was an attempt to bring breastfeeding into the conversation about healthy foods.

In 2018, The Ecology Center also hosted a networking event called Harvesting Health: Food as Prevention. This event brought together stakeholders from Healthy Food in Health Care initiatives with stakeholders involved in community food systems. That same year, the Ecology Center helped create the Healthy Food Playbook which provides resources to hospitals to develop community-based food access programs.

Let Thy Food Be Thy Medicine

The popular, but almost certainly apocryphal Hipocrates phase, “Let thy food be thy medicine”, captures a very real way of thinking about food and health that long predates the Ecology Center and Hipocrates. Archaeologists in China, for instance, uncovered a 2,400 year old medical text titled Recipes for Fifty-Two Ailments--a distant relative of the kinds of food therapy practiced in China today. In the U.S., however, medicine and nutrition have often been treated as separate realms. In the last several decades, more widespread understanding about the connection between diet and chronic disease has pushed many in healthcare to rethink the role of food in medicine. For the last almost two decades, the Ecology Center has played an important role in bringing wellness and food into the same conversation through their work with hospital and community food systems. They have worked with hospitals to source healthier and more sustainably grown food [LINK]. And they have helped Detroiters in need to gain access to the city’s farmers markets.

Just like nutrition and medicine, urban food access and environmentalism have also not always been part of the same conversation. As an organization both influenced by and promoting the environmental justice movement, the Ecology Center has worked to address race and class-based disparities in access to healthy and safe places to live.