See a related article from the Ecology Center's website, Sharing the Bounty: Community Organic Gardening and Healthy Local Food

3. Community Organic Garden

In the 1950s, most Americans considered the use of pesticides, herbicides, and inorganic fertilizers to be innocuous remedies to daily ails. Dismantling that perception, scientist Rachel Carson's chilling account Silent Spring exposed to the general public the dangers imposed on the environment by the ubiquitous usage of pesticides. According to Carson, although pesticides proved remarkably effective at their intended job, they also unintentionally damaged other parts of the environment. Her scientific-based claims frightened people across the country and changed the way the American public perceived pesticides. Her work and the work of environmental activists in the 1960s led to a widespread upheaval of chemicals and a new environmental conscious. Even then, many homeowners did not believe that one could raise a viable vegetable garden without the use of chemicals and continued to rely upon them into the 1970s.

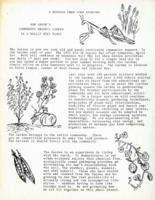

Together with students and faculty from the University of Michigan, local citizens, and Washtenaw County farmers, the Ecology Center and the University of Michigan School of Natural Resources sought to change that perception by demonstrating to the Ann Arbor community the viability of an organic garden. The idea came from a similar project at the University of California in Santa Cruz, but the cold winters and warm summers of Ann Arbor offered the opportunity to experiment with organic methods and technologies under different conditions and to test the viability of new crops. In February, Dr. Robert Zahner, a U-M professor in the School of Natural Resources, delineated the plans for the Garden to a public audience during a seminar on campus. The Garden would be an experimental space for volunteers to raise a garden in which manure replaces fertilizers, birds replace insecticides, and other ecologically friendly practices replace hazardous artificial ones.

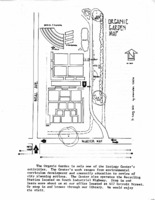

In April 1971, the University provided a seven-acre plot of land on North Campus and a one-year grant for the establishment of the Garden. Located at the corner of Beal and Glacier Way on the University’s North Campus, the seven-acre experiential classroom provided locals with a space to test ecologically-friendly gardening and to unite with a diverse group of people to work towards an environmental cause. From fruits, vegetables, and flowers to bees, fish, and goats, the plans included a diversity of species as well as composting bins, a weather station, and a tool house and shelter. Local citizens made countless contributions, including organic materials for composting and mulching, trees, flowers, seeds, tools as well as their advice and their time. On the same day that the University officially approved the project, the organizers announced the victory to potential volunteers and reminded them of upcoming events, including a seminar on natural foods, two work days at the site, and the Dig-In on May 1st, the first groundbreaking and digging to prepare the land.

"The Garden is beautiful on paper and in our minds--work and care will make it a beautiful reality both physically and psychologically.”

The organizers knew that a centralized organizational structure and a large body of workers would be essential to the Garden’s success. A project director, a garden manager and a work-study student led the coordination efforts, each working about 30 hours per week to assist with the daily operations of the garden as well as to plan special events for educational purposes. To further assist in these efforts, there were eight committees in the beginning, each assigned their own task: overall garden layout, tool shed, tools, flowers and vegetables, herb garden, lawn, bird garden, and composting. In the next year, more committees for garden ecology, public relations, and education would form to meet the expanding needs of the Garden.

In the first year, over two hundred workers who ran the gamut of society, from pre-school children to retirees, helped in the Garden, and over five thousand others visited to learn about the project. Volunteers assisted with many tasks, including plantings, weedings, thinnings, mulchings, watering, and insect control. Each worker had the opportunity to share in the produce while gaining valuable knowledge of organic methods to try in their own gardens. To a journalist from the Michigan Earth Beat, John Remsberg, the first garden manager, recalled a story about a group of young people who visited from the juvenile court:

At first they all shuffled around with sour expressions on their faces, and I was uncertain how I could relate the garden to these young people. None of them wanted to work and get dirty. Then one of the young girls started digging a melon hole and a few minutes later, they all wanted to show that they could do it better...The group stayed all morning and learned a few of the basic concepts of organic gardening.

Although the Garden was a technical venture, it was also an experiment with changing the way people understand the environment and their place within it. The Garden was "the doorway to a new way of life, a way of life in which man is the caretaker of the Earth instead of its self-appointed master." The first Earth Day in 1970 stressed that modern life--with its mass consumerism, throwaway mentality, and insistence on convenience--threatened the environment. As John Remsberg, the first garden manager, wrote in the Ecology Report in 1972, the organic garden embodied the possibility of changing that way of life by offering "healthy and meaningful experiences to people who are aware of their unhealthy and meaningless life styles."

With the publication of "Organic Force Realizes Its Potential in Ann Arbor" in Rodale's Environmental Action Bulletin in February 1972, Ann Arbor's community garden caught the attention of the Bulletin's national readership. In the coming months, letters from across the country poured in to the Ecology Center's main office, expressing excitement, asking questions, and proposing ideas for similar projects in their own communities. In the coming years, the organic gardening concept spread across the nation, as communities sought to cultivate healthy plants, to revive community spirits, and to maintain the spirit of environmental activism from 1970.

In this video, Mike Schechtman, former director of the Ecology Center, remembers the origins of the project, the collaboration between the Ecology Center and University faculty, and the project's growth into a larger community gardening movement in Ann Arbor.