Demanding Stronger Fish Advisories

Beginning in 1986, US states bordering the Great Lakes and the Canadian province of Ontario had begun working on uniform advisory guidelines for fish consumption. During the 1990s, new research into the behavioral effects that toxins had had on childbearing women and their children led to a dramatic increase in the number advisories about Great Lakes fish. By 1997, Ontario and every US state but Michigan had signed onto the guidelines.

The results of a longitudinal study coordinated by Dr. Thomas Darvill and presented at the Ecology Center’s conference “The Environmental Connection: Rising Rates of Breast Cancer, Reproductive Disorders and Children’s Disease" provided cause for concern about eating fish from the Great Lakes. The findings revealed that maternal consumption of fish contaminated with a range of persistent chemicals led to detrimental behavioral effects on the health of newborns and children. Prior to this study, little was known about the behavioral implications for humans exposed to these persistent chemicals as infants and children. Darvill's study had tested nearly 700 newborns and found abnormal reflexes, less mature autonomic responses, and less developed attention to visual and auditory stimuli in the babies born to mothers who consumed high amounts of Lake Ontario fish.

Tracey Easthope and Mary Beth Doyle refute misinformation about fish advisories in a June 1997 letter to the Lansing State Journal.

Organizations like the Michigan Environmental Council were skeptical of Governor Engler's reluctance to adopt the advisory. In a letter addressed to the Council of Great Lakes, the governor argued that, in addition to potential economic setbacks caused by limiting the fishery, Michigan's existing advisories were more protective than levels set by the FDA for supermarket fish. In their rebuttal, the MEC's Carol Misseldine countered that the FDA levels were not designed to protect frequent consumers of sportfish, that they were not based on the latest evidentiary science, and that federal regulations only applied to cancer risks. Furthermore, proponents of stronger advisories argued, existing regulations did not consider the vulnerability of sensitive populations, such as pregnant women and children, to persistent toxins. In refusing to adopt the advisory, Engler was ignoring the advice of scientists, physicians, toxicologists, his advisory board, and every other Great Lakes state. In addition, the governor chose to overlook evidence showing that children of women who continued to eat contaminated fish from the Great Lakes had more learning and developmental difficulties when compared with other children.

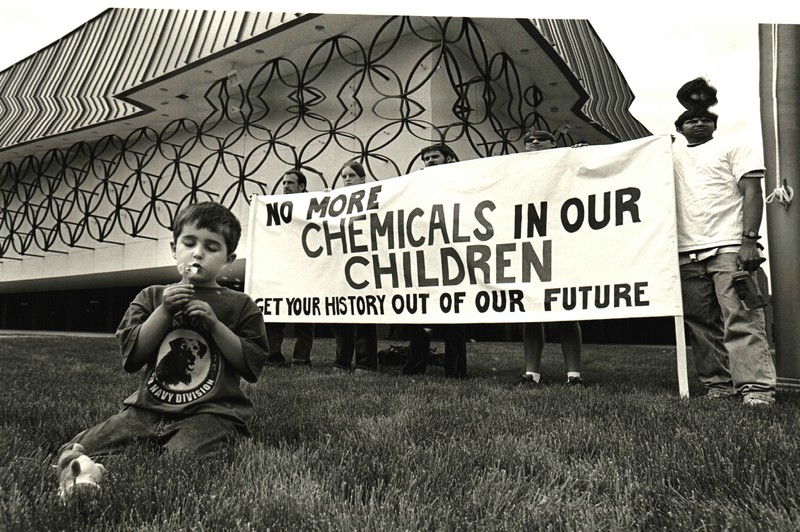

The US Environmental Protection Agency warned Michigan that they would publish their own warning if the state did not act. State Representative Mary Schroer, who represented west Washtenaw County, announced a bill that would force the state to adopt the Uniform Advisory. This bill passed in the House 101-4 but faced a challenge in the Senate. This is where the EC stepped in. The EC, working with the National Wildlife Federation, the Michigan Environmental Council and other environmental groups, pressured Michigan to adopt more restrictive health advisories about the risks of eating Great Lakes fish. They met with public health officials under the Engler Administration, and when direct appeals didn’t work, they started the Paper Plate Campaign.

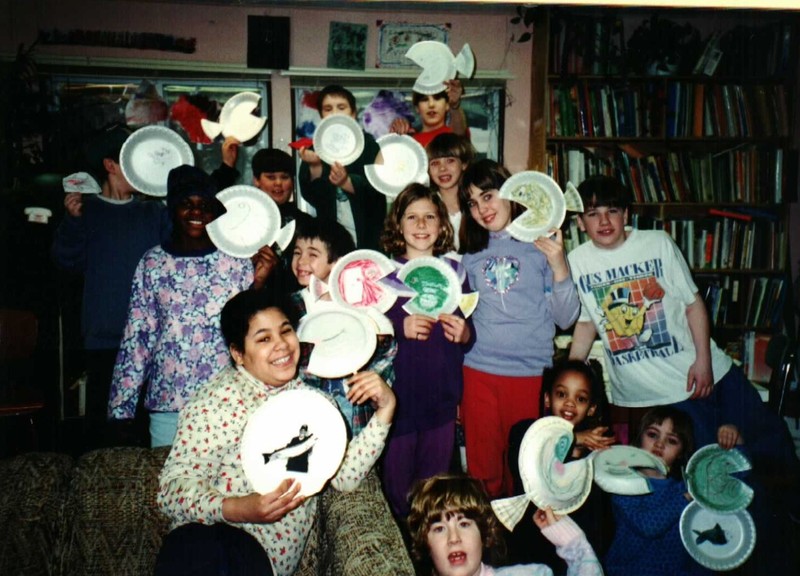

Paper plates were an unconventional form of activism. In February 1997, the EC advertised the campaign in their newsletters and encouraged everyone in the community to decorate a paper plate with a picture of a fish and a personal message about the need to adopt the Uniform Fish Advisory. They even suggested possible slogans such as “we need good advice, not fish tales,” “don’t play politics with our health,” and “what you don’t know CAN hurt you.” A significant volume of paper plates made their way to Lansing where they were noticed by the state. The EC used the successful campaign to strengthen fish advisories and stipulate the posting of warnings at fishing sites, but it took a lot of effort and participation from the community and EC staff.