Dow Chemical and Corporate Accountability

In the 2000s the Ecology Center and their partners consistently campaigned against the interests of large corporate entities, none quite as infamous as Dow Chemical, who had been producing chemicals since Herbert Henry Dow began extracting bromine in Midland, Michigan in 1897. In 2007, Dow was the world’s “largest producer of chlorine and chlorine-based products, the largest producer of chlorinated pesticides and solvents in the U.S., and the planet’s largest producer of chemicals used to produce PVC." This accomplishment came at the expense of thousands of residents across the globe who suffered the adverse health effects from Dow’s chemical facilities, which produced everything from Agent Orange to pesticides to Saran Wrap. For the Ecology Center, the fight to promote health and justice necessarily meant taking on Dow’s attempts to sidestep their own obligations and in the 2000s notably organized against their dioxin contamination scheme and inaction in Bhopal, India.

Dow's Dioxin "Cover Up"

Before the early 2000s there was little public information available regarding dioxin, a toxic chemical and corcenogene, contamination around Dow’s Midland Headquarters, which the state of Michigan had been investigating since 1995. In the spring of 2000, a wetland remediation investigation by General Motors revealed high levels of dioxin downstream from Midland in the Tittabawasee River. This sparked the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) to conduct their own studies, which confirmed that dioxin in the floodplain of the Tittabawasee and Saginaw Rivers had reached levels 80 times that of the state’s cleanup standards. This remained unbeknownst to environmental groups who had been actively seeking such information until early 2002, when an anonymous whistleblower faxed the Ecology Center a map of the contaminated sites and their recorded dioxin levels. These ranged anywhere from 39 to over 7200 parts per trillion even though the state’s residential cleanup standard then was 90 parts per trillion, while the federal action standard was 1 part per billion – which many tested sites also exceeded. By this time the Ecology Center and the Michigan Environmental Council had already petitioned the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry to conduct their own independent study. Their letter stated,

“If history is any guide, the company can be expected to take every step possible to reduce or eliminate their liability, to downplay the threat, to delay action and to influence politicians and agency heads towards that agenda.”

The ATSDR complied but the results of their investigation were not released until environmentalists submitted a Freedom of Information Act request to the local DEQ office. This FOIA package not only confirmed the severity of the dioxin contamination, but also included internal emails indicating the MDEQ’s awareness of the issue and non-commitment to quickly begin cleanup efforts, even though as early as November 2001 department deputies had agreed that Phase II of cleanup should begin.

After these high dioxin levels were discovered, the director of the MDEQ at the time, Russell Harding, blocked further dioxin testing and sought to suppress a health assessment calling for aggressive action. Harding also directed MDEQ staff to weaken the state’s cleanup standard for dioxins, which some staffers actively disagreed with. Internal mails revealed one staffer stated Harding’s decision did not “reflect the best available information” while another staffer said the standards should be toughened, not weakened, based on emerging science. After the disclosure and controversy of the MDEQ documents, Harding said in a Chemical Policy Alert article that MDEQ would not weaken dioxin standards until the EPA released its long-awaited reassessment on dioxin, yet still proceeded to release new initiatives to increase the dioxin standard from 90 to 150 ppt. The EPA then released its 12-year scientific reassessment of dioxin risks which only validated environmentalists’ concern. Emerging scientific evidence suggested the chemicals could cause birth defects, neurological delays, and chronic ailments.

Not only did Harding attempt to weaken dioxin standards, but internal emails also revealed to activists that indicated that MDEQ was in collusion with Dow to create a proposal that would create a designated “dioxin zone” in Midland and effectively relieve the company of any obligation to clean up the toxic chemicals. Assistant Attorney General Robert Reichel later acknowledged the proposal had no legal foundation. Despite its shaky legal standing, in November of 2002 the “sweetheart deal” between Dow and MDEQ was made public when Harding attempted to expedite its implementation before the new state governor took office. The “Corrective Action Consent Order” drafted by DEQ in consultation with Dow substituted a standard of 90 ppt with 831 ppt of dioxin in soil, far above the 90 parts per trillion cleanup DEQ standard. The standard would initially apply to the Midland area, but could later be extended to other contaminated areas of the state.

In response to these emails, the Ecology Center and their partners not only “wrote key members of Congress and the assistant administrator of a federal toxic substances agency demanding a probe of Harding’s actions,” but demanded the MDEQ take certain actions. Together with the Michigan Environmental Council, Environmental Health Watch and Lone Tree Council, they demanded:

- Immediate action to protect children from exposure to dioxin in parks and residential areas along the Tittabawassee River to its congruence with the Saginaw River.

- Release of the public health assessment of the risks posed by contamination in Midland and the Tittabawassee River flood plain.

- Immediate state authorizationfor a more detailed investigation into the extent of dioxin/furan contamination in the Tittabawassee River, and determination as to the source or sources.

- State authorization for development of a cleanup plan.

- Federal and Congressional investigation into the failure of MDEQ, the Department of Agriculture, and Department of Community Health to inform local agencies, and to address a major, public health risk in a timely fashion.

In December 2002, a coalition made up of the Ecology Center and other concerned citizens and environmental groups petitioned the MDEQ shortly before filing a suit to stop the deal, which was set to be finalized within the week. Chris Bzdok, the attorney representing the coalition summarized the party’s feelings stating, “the DEQ’s proposed action is clearly unlawful. The agency has failed to follow law and rules in drafting an order that seems designed primarily to serve the interests of Dow Chemical Company, not the public health.” An Ingham County judge ordered the hearing on the consent order with MDEQ, which effectively opened the door to legal challenge of the deal. Judge William Collette ruled on the petition by the coalition, saying even if the proposed Consent Order was finalized by the outgoing Engler Administration, it could still be overturned if found to be illegal during an ordered hearing in January, which to the relief of activists, it was.

Despite this major victory, the struggle continued for activists and affected citizens who were eager to see the dioxin cleaned up. In June of 2004, the House Appropriation Committee approved the new DEQ budget which eliminated the Hazardous Waste Management Division and reduced staffing and funding. This meant the dioxin cleanup efforts in Midland were essentially halted. Soon after, Tittabawassee River residents, represented by the Tittabawassee River Watch and the Lone Tree Council, and residents from area townships and the City of Midland met with Governor to discuss the need for the state to uphold its cleanup standards in the face of pressure from Dow Chemical. The Ecology Center later joined other environmental groups in criticizing an agreement between Dow and the Grahholm administration as it failed to deliver a cleanup plan of dioxin contamination in the Saginaw Bay basin. The severity of the dioxin contamination only increased when a year later Dow funded a study of dioxin contamination that found that consumption of fish and wild game and living in contaminated areas resulted in increased levels of dioxin and related toxic chemicals in blood.

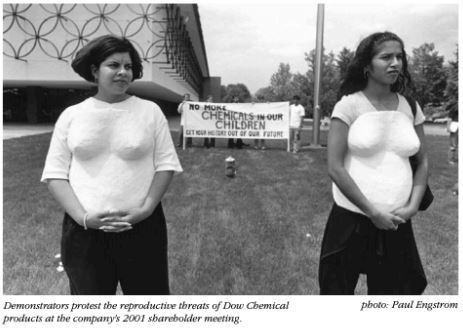

By 2007, Dow shareholders had begun to take notice of the mounting desire from concerned citizens to see the dioxin cleaned up when they approved a resolution by 21% requiring Dow to report on its cleanup efforts in Midland. In 2008 and 2009, shareholders again voted for similar measures. Though only a minority of shareholders voted in favor, similar resolutions in the past had only garnered between 3-8% approval. This increased approval though was likely connected to the class lawsuit that was underway at the same time. Several years prior, Saginaw Circuit Judge Leopold Borrello approved a request from some 2,000 Tittabawasee River residents seeking class action status in an already underway suit against Dow, which was seeking $100 million in damages and claimed dioxin contamination threatened residents’ health and lowered property values. By the end of the decade the suit was in front of the Michigan Supreme Court.

Despite the turbulent decade, environmentalists were optimistic in 2009 when a Special Envoy from the office of the new EPA Administrator Lisa Jackson met with activists during a “fact-finding mission” regarding the dioxin contamination. This came after environmental groups sent a letter to the new administration to protest “closed door negotiations with the giant chemical company launched in the closing days of the Bush Administration.” Senior Policy Counsel, Robert Sussman, met with representatives of the Ecology Center and the Lone Tree Council among other organizations and local residents. By this time, the dioxin contaminated areas were “one of the worst sites in the country.” Not only this, but the “highest levels of dioxin in the nation [were] found here, contaminating the entire food web.” The 2000s were raught with victories and setbacks for activists fighting Dow’s dioxin contamination. Though the struggle continued into the 2010s, environmentalists had proved by then their dedication to the fight.

The Ecology Center Goes International

In 2001 Dow purchased Union Carbide, the company directly responsible for the Bhopal Disaster, the worst industrial accident in history. This effectively meant they took on the responsibility for the cleanup efforts in India. The Bhopal Disaster was a gas leak incident that occurred at a Union Carbide India Limited pesticide factory on Dec 2-3, 1984. The gas released was methyl isocyanate (MIC) which is extremely dangerous and upon exposure can cause coughing, eye irritation, vomiting, breathlessness, burning in the respiratory tract, and death. The immediate death toll from the incident remains up for debate ranging from ~3,000-16,000 though over half a million people were exposed in total and suffered long term health effects.

Bhopal Activists came to Dow shareholder meetings in 2003 to demand accountability for the Carbide gas disaster. Activists and survivors spoke at the meeting about the reproductive and other medical issues/illnesses related to the disaster. That same year, the Ecology Center and other Michigan based groups sponsored “Indecent Acts - Demanding Corporate Accountability,” an organizing workshop and conference on Dow Chemical. Here, Bhopal activists once again highlighted the gas disaster and set light on the persistence of toxic pollutants in Bhopal, which continued to have lasting impacts on those who lived there. Organizing continued throughout the year and on December 3rd, 2003 students from 25 different high schools, colleges, and universities across the US participated in protests against Dow as a part of the first ever Global Day of Action Against Corporate Crime.

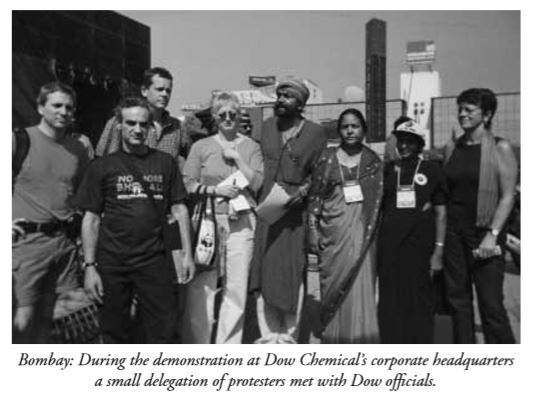

In January 2004, the Ecology Center’s Environmental Health Director, Tracey Easthope, travelled to India to meet with Bhopal survivors and address the World Social Forum. Easthope was accompanied by several other activists including representatives from the Lone Tree Council, the Environmental Health Fund, Pesticide Action Network and Beyond Pesticides. The International Campaign for Justice in Bhopal and the Dow Accountability Campaign organized events and speeches at the forum to discuss Dow’s accountability for the cleanup and remediations for survivors. Though the Bhopal Disaster was in center stage for the events, representatives from across the world also attended as Dow were responsible for several other health crises. These included residents from Midland, Michigan, who suffered from increased dioxin levels, representatives from Vietnam who suffered adverse health effects from Dow’s production of Agent Orange there and Dow factory workers from South Africa. During this trip, Easthope joined hundreds of women from Bhopal who held a demonstration outside Dow Chemical’s headquarters in Bombay and notably shouted, “hit Dow with a broom!” or “Jhadoo Maro Dow Ko!”

While in India the cohort of activists also toured inadequately constructed and dangerous chemical factories with other activists and visited the Sambhavna Clinic in Bhopal. While touring the defunct Union Carbide factory where the disaster took place, Easthope notably encountered what she witnessed, which included “mercury beads in the soil, open containers of DDT, a series of huge warehouses with uncontained bags of pesticides and pesticide ingredients laying around, a chemistry lab with bottles of chemicals strewn about, used plastic gloves,” etc. Having witnessed this and visited the Sambhavna Clinic, where residents were still being treated for injuries relating to the disaster, illuminated for the Ecology Center and other activists the extent to which Dow were responsible for injustice outside of what they’d actively seen in Michigan.

Back in the States, activism only continued when two Bhopal survivors, Rashida Bee and Champa Devi Shulka, led a group of environmental activists and ‘crashed’ Dow’s 2004 shareholders meeting. Supporters held a demonstration and Easthope once again relayed the Ecology Center’s support for the cause when she read a resolution on the behalf of Bee and Shulka asking Dow to report on how the company’s liabilities in Bhopal may affect growth and stability in the rest of India and Asia. While in the US, Bee and Shulka also gave talks about their experiences in Bhopal to raise awareness of the disaster’s legacy, even making stops to talk in Ann Arbor and Detroit. That same year, Dow faced the heat from its own investors when Innovest Strategic Value Advisors Inc. released a report on investor risks pertaining to Dow. The report included generally underreported risk assessments regarding Bhopal, Agent Orange, dioxin contamination in Michigan, their $10.7 billion debt, semiconductor worker liability, and market risks for organochlorine investments.

Throughout the 2000s, activists consistently worked to raise awareness of the health consequences that came from Dow’s industrial chemical facilities and demand accountability from the company. Though the consequences of the Bhopal Disaster could hardly be forgotten, the work of activists across the globe took an important step in bridging the gap between local and global activism.