See a related article from the Ecology Center's website, The Long Legacy of John Engler’s Environmental Deregulation How Michigan Wrote the Playbook for Trump’s Federal Rollbacks

The Engler Administration's Environmental Rollbacks & Poor Standards

John Engler, who had served in the Michigan legislature as the Senate Majority Leader, was elected as the 46th Governor of Michigan in 1990 and served three consecutive terms, leaving office in January of 2003. A member of the Republican Party, Governor Engler’s gubernatorial tenure was marked by welfare and education reforms, income tax cuts, privatization of state services, and most notably, environmental deregulation. While environmental protections and rules were eased throughout his time in office, many of the Engler Administration’s rollbacks occurred in his final term, especially after his Lieutenant Governor lost the 2002 Gubernatorial election to the state’s Democratic Attorney General, Jennifer Granholm.

While the Engler Administration instituted many changes, his relaxation of energy efficiency standards in the 1990s are especially notable due to the long-term impact they continued to have on Michigan’s energy sourcing well after he left office. After receiving complaints from electric utilities, the Michigan Public Service Commission under Engler eliminated a requirement that Michigan’s two largest investor-owned utilities spend more than $80 million per year on energy efficiency programs. They also helped persuade the state legislature to repeal a decision they had made to adhere to requirements outlined in the national Model Energy Code for energy efficient design of new residential buildings. This was to benefit homebuilding companies, but set up Michigan residents to pay more for heating and cooling in their homes for decades to come.

In general, many of the environmental rollbacks Engler installed were more convenient to big businesses and corporations than they were beneficial to the environment or public health. For example, the Michigan Strategic Fund Board under Engler approved the issuance of $35 million in tax exemption bonds to Waste Management of Michigan in 2001 for the purpose of expanding their landfills in Macomb, Leelanau, Wayne, Crawford, Clare, and Ottawa counties. Waste Management was the largest disposal firm in the world at the time, with 284 active landfill sites in North America. While this in of itself is not an example of environmental deregulation, it highlights Governor Engler’s prioritization of corporations over protecting the public health of citizens and Michigan’s environment.

The Michigan Department of Environmental Quality’s Issuance of an Illegal Air Quality Permit to General Motors

In the autumn of 2001, the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) under the Engler Administration issued an air quality permit to a new General Motors (GM) assembly plant in Delta Township, located just outside of Lansing. The permit allowed the plant to emit up to 1,275 tons of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) every year. VOCs are notoriously harmful to the environment as well as human health; they are known to damage the liver, kidneys, and nervous system, pose a cancer risk to humans, and contribute substantially to the formation of ground-level ozone, which was responsible for triggering thousands of asthma attacks in the early 2000s.

The Ecology Center and other groups quickly picked up on a major issue with the MDEQ-issued permit: it did not require the installation of low-cost pollution control technology, which was legally mandated by the Clean Air Act. The best low-cost pollution control technology available at the time would have eliminated between 250 and 400 tons of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in emissions annually. Mike Garfield, the Director of the Ecology Center, said in a 2001 statement that “given the availability of cost-effective emission control technology, which is clearly required under the Clean Air Act, it is irresponsible for the MDEQ to not hold GM to the same pollution standards that it holds other companies in the state.”

In order to hold Engler’s MDEQ to the federal standard expected of them, in late October of 2001 the Ecology Center and the Michigan Environmental Council filed an administrative appeal to the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regarding the GM air permit, arguing that it allowed “too much pollution.” In order to expedite the process, the Ecology Center filed their appeal directly with the EPA’s Environmental Appeals Board. The Board ruled in support of the Ecology Center’s appeal on March 6 in the following year, stating that the MDEQ-issued permit “did not meet federal requirements.” The EPA agreed with the Ecology Center on five out of six counts and remanded the permit back to MDEQ for corrections. “We have felt for a long time that the state has been allowing large corporations to write their own permits and ignoring its responsibility to protect the public health,” said Jeff Gearhart, the Ecology Center’s Campaign Director, in a statement on the matter. “This time, though, the state failed both the people and GM by issuing a bad permit, and the EPA stepped in.”

MDEQ spent the next few months working on a new permit for the General Motors facility. When they reissued the air quality permit in August of 2002, though, the Ecology Center recognized that almost nothing had changed: the new permit still allowed them to release more than 1,200 tons of harmful pollution per year, all the while without requiring them to install, as described in an Ecology Center press statement, “cost-effective new equipment that would reduce tons of paint shop emissions from Lansing area air.” The controls advocated by the Ecology Center during their appeal process would have saved 235 tons of VOCs, or approximately 20% of the pollution allowed by MDEQ, annually.

Since the permit had been modified to make ‘improvements’ on pollution levels, the Ecology Center was not in a position to appeal the MDEQ permit to the EPA again. While the changes MDEQ made did make slight improvements to the new plant’s air pollution allowance, the fight still felt like a loss for the Ecology Center. However, despite the persistence of the Engler Administration to continue to create poor environmental standards, the Ecology Center was tenacious enough to fight them through this loss and the rest of Governor Engler’s tenure.

MDEQ’s Cover-up of Dow Chemical's Dioxin Pollution in their “Sweetheart Deal”

It was not until January 2002, though, that the Ecology Center and their allies discovered some of the most egregious efforts the Engler Administration had undertaken to assist corporate interests over the health of Michigan citizens and environment. They filed a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request about dioxin levels in the floodplain of the Tittabawasee and Saginaw Rivers, near many parks and residential areas, since the state would not release the information to them. The documents the Ecology Center obtained indicated that dioxin levels in that region were 80 times higher than the state’s cleanup standard requirement and that MDEQ had discovered this two years prior in 2000. They also noted that the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality Director under Engler, Russell Harding, blocked further testing in the area and sought to suppress a health assessment from his own department calling for aggressive action.

The levels of dioxin ranged from 39-7200 parts per trillion in the floodplain, which was 80 times higher than the state’s residential cleanup standard of 90 parts per trillion. This indicated to the community that the levels of dioxin present were incredibly dangerous to them and their environment. The federal action standard was 1 part per million, which many of the test sites also exceeded. The documents plainly stated that Harding had overrode his own MDEQ staff by ordering them to weaken the state’s cleanup standard for dioxins in new rules, as a staffer had noted that Harding’s decision did not “reflect the best available information” while another employee noted that the standard should be toughened, not weakened, based on emerging scientific evidence.

While the source of the dioxin contamination was unknown, the Ecology Center, as well as some MDEQ staffers, believed that it likely stemmed from a 1986 flood at Dow Chemical Company’s Midland plant and headquarters. The flood had been triggered by a record downpour and caused as much as 30 million gallons of diluted chemicals to spill into the Tittabawsawee River, which winds through most of Midland before emptying into the Saginaw River and Bay. Dow Chemical Company, which was and remains one of the largest chemical companies in the world, produced more than 500 chemicals, plastics, and resins at their Midland location in the 1980s.

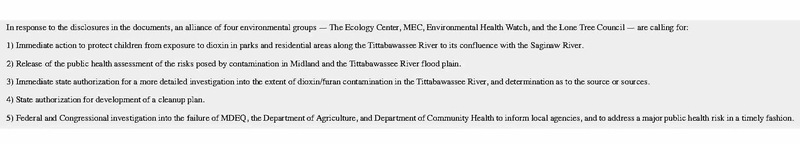

By March 2002, after the disclosure & controversy of the MDEQ documents, Harding said in a Chemical Policy Alert article that MDEQ would not weaken dioxin standards until the EPA released its long-awaited reassessment on dioxin. The EPA study he was referring to was a 12-year scientific reassessment of dioxin risks that validated the public’s concern about them, as emerging scientific evidence showed “that many dioxin compounds can cause birth defects, neurological delays, and chronic ailments.” However, rather than wait until that was completed like he had publicly stated, he shortly after proceeded to release new rules that would weaken dioxin from 90 to 150 parts per trillion and would lock those rules into place, making it much more difficult to change them in the future. In response, the Ecology Center, Michigan Environmental Council, Environmental Health Watch, and Lone Tree Council demanded that MDEQ take certain actions to reverse the damage they had done. “With a wave of the wand, Harding is trying to ‘declare’ some areas clean instead of actually removing dioxin,” said Tracey Easthope, who served as the Ecology Center’s Environmental Health Director, in a statement at the time. “This could save Dow millions of dollars but cost the people of Michigan tens or hundreds of millions of dollars in cleanup and health care costs.”

On October 4th, 2002, the Ecology Center joined citizens in Saginaw County and other environmental groups in a letter addressed to the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, the Michigan Department of Community Health, and MDEQ, outlining how they rejected a Dow-sponsored study on the health impacts of the contamination the company had caused. They demanded an “independent review and immediate public health protection” in the letter.

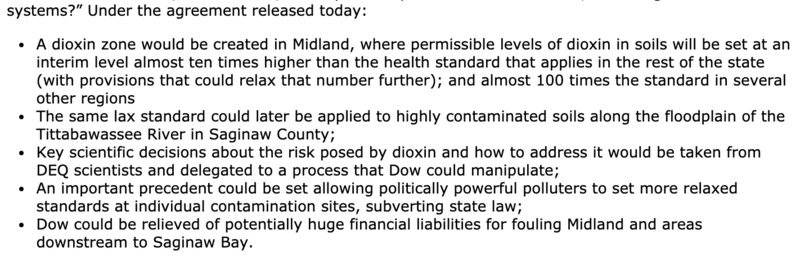

Later that month, Saginaw County residents, with the help of the Ecology Center and other environmental groups, discovered internal documents that detailed how MDEQ was attempting to collude with Dow Chemical to create a ‘dioxin zone’ in a deal that state of Michigan attorneys had warned was “illegal” and “fatally flawed.” In a press release, the Ecology Center argued that “top management of the Michigan DEQ is working hand-in-glove with the Dow Chemical Company to craft an agreement relieving the company of costly dioxin cleanup requirements and exposing the public to dioxin contamination.” The deal, which would establish four understandings (outlined in the image on the left) between Dow and MDEQ, would evade Dow of nearly all their responsibility in cleaning up the dioxin contamination they had caused. Furthermore, the documents revealed that the Engler Administration was working to fast track the deal before the new Governor would take office in January. “This has always been about what Dow has wanted. It has never been about what was in the best interest of public health or the watershed,” said Curt Dalton of the Tittabawassee River Watch after reading how MDEQ and Dow had a desire to get something in writing since the next Governor might not be as “favorable” to the company. “Dow’s political influence is immense.”

On November 8th, the “corrective action consent order” drafted by MDEQ in consultation with Dow was made public, initiating a 30-day public commentary period before it was finalized. The agreement substituted a dioxin standard of 90 parts per trillion with 831 parts per trillion in soil, far above the 90 parts per trillion MDEQ cleanup policy. The proposed standard was written to initially apply to the Midland area, but could later be extended to other contaminated areas of the state. Harding was quoted on the matter saying that cleanup efforts “would be a huge expense for them for what they think is not money well-spent.” Yet again, the Engler Administration had proved that relieving Dow Chemical of their liability for massive contamination of one of the largest watersheds in the Great Lakes basin was more important than risking the public’s increased exposure to higher levels of a “potent developmental and reproductive toxin” like dioxin.

Citizens and environmental groups alike decided to take action in order to prevent the deal from going into effect on December 10th. They filed a petition under the National Resources and Environmental Protection Act on December 2nd, seeking to intervene in the order and request a delay in the decision until MDEQ weighed evidence “opposing a change in the standard.” Additionally, they also issued a formal request to MDEQ asking for an extension of the public commentary period on the plan in order to give citizens a chance to present thorough documentation challenging the agreement. MDEQ quickly rejected their request. Recognizing that their efforts might not make a difference until after the deal was finalized, a coalition of citizens, the Ecology Center, and 5 other environmental groups filed suit against MDEQ to stop the deal. “DEQ’s proposed action is clearly unlawful,” said the coalition’s attorney, Chris Bzdok, in a press release. “The agency has failed to follow law and rules in drafting an order that seems designed primarily to serve the interests of Dow Chemical Company, not the public health.” Since the state attorney’s office had criticized the corrective plan in the past, MDEQ chose to cut out the Department of the Attorney General and spent $10,000 in taxpayer money to hire outside counsel. When they filed on December 5th, the Ecology Center knew their only hope of preventing the implementation of this deal before Engler’s term ended was a court injunction.

On December 9th, 2002 – the last day of the public commentary period before the deal took effect – an Ingham County judge ordered a hearing on the Dow Chemical consent order with MDEQ, opening the door for the Ecology Center and others to legally challenge the deal. The judge ruled on the petition by the coalition, saying that even if the proposed consent order was finalized by the Engler Administration, it could be overturned if it was found to be illegal during a court-ordered hearing scheduled for January.

Tracey Easthope of the Ecology Center said in their press release on the matter: “While we were unable to convince the court to stop the order from being implemented, his ruling paves the way for us to be back in court if this sweetheart deal between Dow and the DEQ is made final.” Without the perseverance and last-minute efforts of the Ecology Center and their partners, this deal may have gone into effect irreversibly just before Governor Engler left office. With grassroots activism the Ecology Center was able to fight Engler until his final days as Governor, preventing him from doing more long-term damage and bolstering his legacy of environmental disregard.

To read more about the Dow Chemical fight, you can go to the “Dow Dioxin Cover-Up” article on our website.

Other Rollbacks & Poor Standards Instituted During the Engler Administration’s Final Years

While Engler’s most egregious environmental controversies stemmed from MDEQ’s relationship to large corporations, his administration changed many other standards in his final years that culminated in long-term environmental damage and policy setbacks.

In 1998, Governor Engler’s Michigan Environmental Science Board (MESB) started investigating whether or not MDEQ’s standards adequately protected children’s health after the state legislature passed an amendment prompting them to investigate. After a year-long study, the MESB issued a major report in February of 2000 that admitted alarming flaws in the state’s pollution risk assessment policies: namely, that state rules failed to account for the effect of multiple chemicals on children’s health. The report suggested that more research was needed to better understand the problem; this went directly against the recommendations of the only two pediatricians members of the MESB. Both doctors argued that action needed to be taken immediately.

The Ecology Center began investigating the issue and conducted their own research on the matter. In August 2002, they released a 20-page report with the Michigan Environmental Council titled “In Guarding Michigan’s Most Vulnerable: Making Michigan a Leader in Protecting Children From Environmental Pollution.” Their research detailed that 108 of Michigan’s pollution policies failed to “adequately protect children from environmental hazards.” The report noted that “children are not small adults” and that pollution that may not harm adults can have both immediate and long-term effects on children, as small doses of pollution “at critical stages of development can be harmful.”

In the conclusion of their report, the Ecology Center urged the next Governor and Legislature to address environmental health threats by “changing state law to make protection of children, rather than full-grown adults, the basis for standard-setting for air, water and waste programs.” They believed this was an urgent and necessary measure to take; children are uniquely susceptible to experiencing harm from chemical exposure due to the fact that they are rapidly developing both physically and mentally as they grow. Standards that may have been safe for fully-developed adults could prove to be very dangerous to growing children, the Ecology Center argued. They also asked the next Governor to follow their four recommendations: crack down on mercury emissions from coal-fired power plants; phase out toxic chemicals that pose unacceptable risks to children’s development; increase efforts to educate parents on how to avoid exposure of their children to pollution; and use the Great Lakes Protection Fund to launch an aggressive research program on children’s environmental health exposures.

During his last year in office, Governor Engler signed Public Act 578 into law, which banned the sale of mercury thermometers in the state. However, this was the only substantive measure Engler took in regards to the elimination and recovery of toxins like mercury. In this interview clip, Liz Brater discusses how the Engler Administration lessened toxin restrictions, which led to a 10-fold increase in cancer risk for Michigan citizens: https://lsa-dss.mivideo.it.umich.edu/media/t/1_nozgv2tu (20:00-21:25).

Article written by Lily Antor, member of the Spring/Summer 2020 Research team.