Negotiating a Cleanup with Gelman Sciences

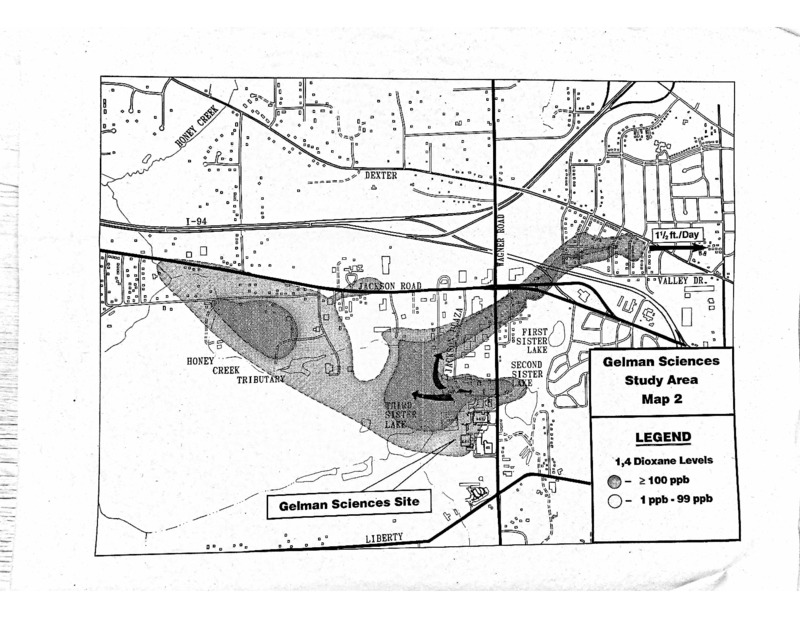

The Ecology Center began its most intensive involvement in the Gelman Sciences clean-up saga by helping represent and inform Scio and Ann Arbor citizens about the hazards of 1,4-dioxane. David Stead, as the Ecology Center's Environmental Policy coordinator, initially sent out information in newsletters regarding the clean-up during the deep-well injection petition in 1986. The organization's most intensive involvement in the issue, however, would only begin in the early 1990s when Ecology Center staff mobilized with the “Gelman Site Citizen Cleanup Review Committee.” When considering pollutants, the Ecology Center operated on the precautionary principle: if a substance could be potentially harmful, the burden of proof should lie on polluters, who must clean the pollution site to the greatest possible extent. To the Ecology Center, “the greatest possible extent” meant reducing the levels of 1,4-dioxane levels down from 100 parts per billion (ppb) to 3ppb throughout the Gelman pollution site.

To Gelman Sciences, however, the scale of this reduction was egregious. At the time, scientific and regulatory frameworks stipulated that up to 100ppb did not pose grave human risks. Charles Gelman also characterized the Ecology Center staff as “extremists” and published an article in one of Gelman Sciences' publications titled “Is Environmentalism a Big Mistake?” He also ridiculed the programmatic purpose of Ecology Center in a letter to Al Gatta, a city councilman in Ann Arbor, when asked the EC “to organize a volunteer fecal police corps to reduce persistent contamination to the Great Lakes.” These attacks escalated after Gelman Sciences allied with the Washtenaw Libertarian Party, who attacked the Ecology Center on the grounds of “accessing the city treasury” and being ideologically predisposed to the over-regulation of businesses. Mailings sent to the Ecology Center’s newsletter recipients presented false allegations and smear tactics against the Ecology Center and Recycle Ann Arbor. In response, the Ecology Center’s Mike Garfield threatened legal action against the Libertarian Party, while starting a “Fight Back Fund” with Ecology Center supporters to minimize Gelman’s misinformation campaign.

The End of a Battle, the Beginning of a Clean-Up

In spite of Gelman’s efforts to undermine the EC's efforts to hold the firm responsible for its pollution, the Ecology Center worked with citizens to achieve small victories towards a general clean-up. In 1992, the City of Ann Arbor reached a compromise with Gelman Sciences to remediate the small contaminated site the in Evergreen subdivision. David Stead, a member of the Michigan Environmental Council who had worked on the Gelman Sciences pollution in the 1980s as an EC employee, played a key role in brokering this compromise. He recalls the experience in a July 9, 2019 interview:

"There were some nasty politics going on, so this all came about, and I said 'Maybe I can help negotiate something here,' and the mayor said, 'Yeah, please, go ahead and try that'... I had been doing this at the state legislature, negotiating particularly the Polluter Pay regulations and negotiating through all of those very difficult issues. [I had] a lot of experience in kind of negotiating toxic materials regulations and approaches."

As for the larger clean-up area, near Third Sister Lake in Scio Township, Gelman Sciences proposed to discharge the contaminated water through the Allen Creek stormwater drain into Honey Creek, a tributary of the Huron River. Citizens living adjacent to the Huron River, as well as the Ecology Center, vehemently opposed the plan and it was rejected by Ann Arbor Mayor Liz Brater for simply moving the contamination rather than removing it.

In 1995, a “Unified Plan” forced a compromise clean-up plan that would treat the contaminated water down to 77ppb worth of 1,4-dioxane. Though not reducing pollution to a level that that the Ecology Center had lobbied for, this agreement finally began the clean-up process - over a decade after the groundwater contamination was initially discovered. The contamination site remains an issue for Scio Township today, as 1,4-dioxane levels remain high in the areas surrounding the Third Sister Lake and Honey Creek.