Fighting Groundwater Contamination

Coalition work was equally central to the Ecology Center’s attempts to fight groundwater contamination in the 2000s. Across southeast Michigan, the safety of residents’ health relied on the safety of their groundwater. By assisting local organizations as they attempted to seek justice, the Ecology Center could empower residents to take action in their own communities and take steps towards achieving health and justice more broadly.

Pall Gelman Incident Continues

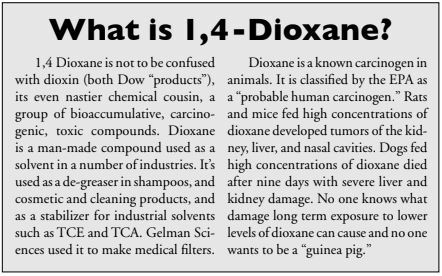

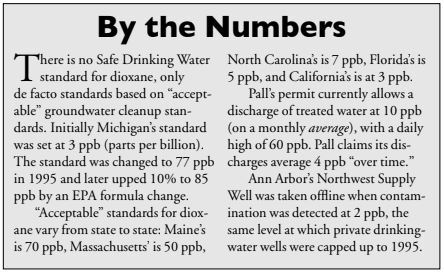

The presense of a 1,4 dioxane plume in the groundwater in Scio Township and western Ann Arbor was first discovered by a University of Michigan graduate student in 1984. The source of the dioxane came from Gelman Sciences (later Pall Corporation), who had been using 1,4 dioxane as a solvent to manufacture ultra-fine medical filters at their Wagner Road facility. The plume posed a significant health risk to local residents especially because the toxic chemical had infiltrated not only the soil, but also local residents’ drinking water and wells. Though Pall made attempts to clean up some of the plume in the 1990s, in 2001 they discovered the plume of dioxane-contaminated groundwater had spread into Unit E, the deepest underground aquifer in the area and was slowly encroaching on the city of Ann Arbor and the Huron River.

A year earlier, Washtenaw Circuit Judge Donald Shelton had given Pall five years (giving them a 2005 deadline) to significantly reduce the dioxane levels. This order had to be abandoned though once it was discovered that the plume was much larger than anticipated. In a September 2004 ruling, Washtenaw Circuit Judge Donald Shelton gave Pall and the Department of Environment Quality (DEQ) 21 days to finish their proposals for a new cleanup plan. Pall’s proposal was to extract contaminated water from a well in Maple Village, treat it, and reinject it. The DEQ opposed this plan because it would allow dioxane to continue to spread in the aquifer even while cleanup efforts ensued. The DEQ’s plan on the other hand was to “[push] for Pall to immediately start the capture of the E-unit plume at Wagner Road. In addition, the MDEQ plan required “leading edge” remediation, which would impose the installation of monitoring wells, purge wells, and pipelines with untreated purge water in neighborhoods with small lots and that have no wells.” Local residents were on board with this more aggressive approach but not so much the residents of Veterans Park who opposed putting disruptive extraction wells and pipelines in their neighborhoods.

At the time, Roger Rayle of the Scio Residents for Safe Water stated to the Ecology Center that both parties were still withholding information and was concerned about the fact that there was still a lack of information on the extent of the dioxane pollution. Rayle also stated that Pall was lying about not knowing about the dioxane levels until 1997 because their samples from 1986 to 1993 “showed some wells in the E aquifer had levels of dioxane above the cleanup standard at the time.”

Concerned that the DEQ’s proposal to capture the dioxane plume would be disruptive to a densely populated residential area and with no guarantee of success, Judge Shelton ruled in favor of Pall’s proposal in 2005. Though Judge Shelton approved Pall’s plan to extract, treat, and re-inject groundwater at a facility near the residential area, he also required that Pall attempt to fully capture the plume. Rayle agreed with Shelton’s decision, but the activist remained concerned about how much dioxane would be leftover and where. Despite this step towards a large-scale cleanup effort, activists continued to seek more aggressive cleanup measures well into the next decade just as dioxane 1,4 indeed continued to spread throughout the area.

Downriver Injection Wells

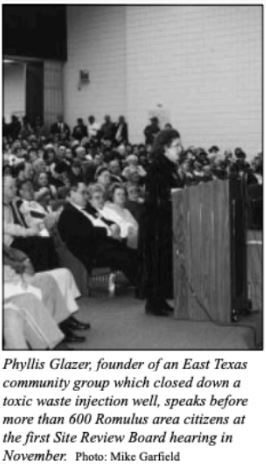

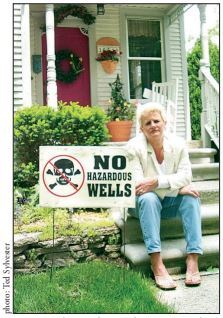

By the start of the 2000s, the Ecology Center and other environmental groups were also already deeply embroiled in a fight to stop the operation of a deep injection well in Romulus, Michigan. Injection wells work by pumping liquid hazard waste into impermeable layers of rock deep underground. Though sound in theory, injection wells possess not only the ability to leach toxic chemicals into groundwater, but destroy natural habitats in their immediate surroundings. In fact, as early as 1989 the US General Accounting Office (GAO) documented 23 cases of drinking water contamination from deep wells injecting oil and gas wastes.

Environmental Disposal Systems (EDS) began construction on several well sites in Romulus, MI in 1990, before they were halted in 1993 after RECAP (Romulus Environmentalists Care About People), with support from the Ecology Center and other activists, won an injunction against the facility for violating zoning laws. The fight between RECAP and EDS went to court in 1999 and concluded with the statement that “EDS’s state and federal permits would override the authority of local land use laws, and allow the company to use the land for waste disposal.” EDS then sued the city for $1 million for loss of future earnings, but the court ruled in favor of the city.

At this time, Romulus and the Detroit area more generally was already severely at risk due to their high concentration of waste treatment and industrial facilities. “According to the Michigan Department of Community Health, there were nearly 40,000 children with asthma in Wayne County, and another 67,000 adults with asthma. In the Detroit area alone, Including Romulus, more than 9,000 individuals died of cancer in 1995. One million pounds of cancer-causing chemicals were dumped into the air and water that same year.” There was a direct correlation between location, amount of chemicals dumped, and the health of the population.

By 1999, EDS moved on to another, properly zoned construction site nearer to Taylor, MI and steadily obtained the required permits from the EPA, the DEQ, Wayne County and the City of Romulus. This new well would be the first in operation serving the Great Lakes region since 1984. That same year, the Citizen’s Site Review Board (SRB), which reviewed EDS’s latest requests for a DEQ construction permit for a hazardous treatment and storage facility. The SRB recommended the request be denied in March of 2000 citing public opposition and environmental concerns. Chief among these were EDS’s plan to construct a hazardous waste facility on wetlands, which violates Michigan’s environmental regulations. The SRB were also concerned about, “the adverse effect the facility would have on property values, future quality development, and community image.” Romulus was already overburdened with toxic waste facilities (as of 1997, the city had one toxic waste facility for every 140 residents) and the overall necessity to construct a new facility was low in the industry. The SRB’s recommendation to deny the permit would’ve halted EDS’s plans to begin operating had it not been for Governor Engler’s decision to change the SRB from a decision-making body to strictly advisory in 1993. Because of this move, the SRB could only make recommendations to the DEQ instead of operating as an independent body. Despite the SRB’s recommendation, the DEQ granted EDS their permit and stated the SRB had not provided significant enough reasons for a denial that could not be mitigated by requiring special conditions in the construction permit.

In response to this decision, a coalition of 20 environmental groups, including the Ecology Center, released a statement in condenouncing MDEQ’s decision to grant EDS a hazardous deep well injection permit in Romulus, arguing it “prove[d] the agency’s continuing dereliction of its duty to protect public health and the environment.” R.P. Lily of RECAP was also quoted stating,

In late June of 2004, EDS came closer to receiving their final operating license on the well when Ingham County Circuit Judge William E. Colette ruled that EDS should have exclusive use of Mount Simon, a massive underground sandstone formation. This came after another company, Sun Pipeline, who had been extracting brine from Mt. Simon had their permit revoked by Judge Colette. The actual injection of toxic waste had been delayed thus far as both companies could not operate at the same time, the reason being if EDS injected hazardous waste, then Sun Pipeline might extract said waste if it contaminated the underground brine. The Michigan Court of Appeals reversed Judge William E. Colette’s decision to revoke Sun Pipeline’s permit and then reversed that ruling again in September 2004. Despite public opposition to the well, the Michigan Supreme Court ruled on August 1st, 2004 that it would not hear an appeal issued by the cities of Romulus and Taylor and Wayne County. In their effort to stop EDS from operating the wells, the municipalities had spent over $2 million dollars in legal fees. In 2004, Bran van Guilder of the Ecology Center wrote,

"Operation of this facility poses a threat to groundwater. EPA claims that no geologic activity will allow the injected wastes to be a threat for at least 10,000 years. However, human activity such as other wells, spills, and accidents could allow the waste to be a threat to groundwater.”

In a stunning development at the end of the year though, the DEQ decided not to grant EDS a license to open the already constructed hazardous waste facility. The construction did not match plans and DEQ found other concerns in a routine inspection. While this did not end plans for the injection well entirely as they were able to begin operating the next year. Not long after though, EDS once again faced more violations (including an above ground leak) and financial issues. Despite EDS receiving a formal “Letter of Warning and Suspension of Operations” from MDEQ on November 2, 2006 for their noncompliance with their Operating License, they failed to resolve their outstanding violations. This led the EPA to issue a Notice of Decision to Terminate, which meant the MDEQ needed to revoke their operating license. Before MDEQ made a final decision in 2009 about revoking their operating license, they held a public input meeting to which activists once again voiced their opposition to the well. Though the residents of Romulus would again encounter injection wells, the 2000s proved to be a decade of successful grassroots organizing.

Additional Sources

"Saginaw (Part 1)," Living on Earth, National Public Radio, Mar. 15, 2002.

"Dioxin Debate (Part 2)," Living on Earth, National Public Radio, Mar. 22, 2002.