Groundwater Education (GEE-WOW!)

Concerns about groundwater pollution formed a unifying thread through many Ecology Center's efforts throughout the 1980s. Campaigning against household toxics and pesticides, and expanding and improving solid waste management efforts all worked to reduce groundwater pollution in southeast Michigan. While these campaigns emphasized short-term environmental remediation, the EC also began to focus its efforts on long-term educational initiatives by the end of the decade. They directed these efforts toward the next generation of Ann Arbor citizens and developed curricula educating Ann Arbor students about the impacts of groundwater pollution.

Environmental Education Before GEE-WOW!

During the 1960s, growing concerns over threats to human health and the natural world spurred an effort among activists and educators to develop new approaches to teaching young people about the environment. Unlike predecessor movements such as nature study and conservation education, environmental education strove to do more than promote respect for the natural world, rather, it emphasized urgency, social responsibility, and problem solving.

At the helm of the new environmental education movement was William B. Stapp, a professor at the University of Michigan’s School of Natural Resources and Environment (now the School of Environment and Sustainability). Working half time for the Ann Arbor public schools and half time for the university, Stapp came to believe that the future health of the environment depended on the education of its youngest stewards. In 1969, Stapp helped establish the Journal of Environmental Education and contributed its first article.

The Ecology Center, founded a year later in 1970, was strongly influenced by the environmental education movement. In the spring of 1973, Ecology Center staff proposed a redesign of Ann Arbor’s outdoor education programming based on the guiding principles of “community problem solving” and “clarifying values.” For more on these early education efforts, see the Ecology Center’s article, Connecting Learning with Action: the Ecology Center’s Recycling Education Program.

Soon after the publication of the first issue of Environmental Education, calls for a robust expansion of environmental education reached the White House. In a report to Congress in 1970, Nixon stressed the need for “environmental literacy...at every point in the educational process.” That same year, Congress passed the Environmental Education Act which established the Office of Environmental Education in the Department of Education.

By the late 1970s, however, the federal government’s interest had waned. Continual defunding of education and political attacks on environmentalism created an educational vacuum which NGOs and university faculty, including Stapp, attempted to fill. In the mid 1980s, a master’s student of Stapp’s, Tara Ward, would head to work at the Ecology Center.

Early Water Education Initiatives

The EC began incorporating the significance of groundwater pollution across existing household toxics and oil recycling campaigns. When toxics and motor oil are disposed of incorrectly the pollutants can enter groundwater supplies and put local drinking water at risk.

In collaboration with Groundwater Education in Michigan (GEM), the EC developed numerous classroom aides and activities for teaching middle and high school students about the effects of groundwater pollution. The most common teaching aide is known as the “flow model,” which illustrates how contaminants move through groundwater.

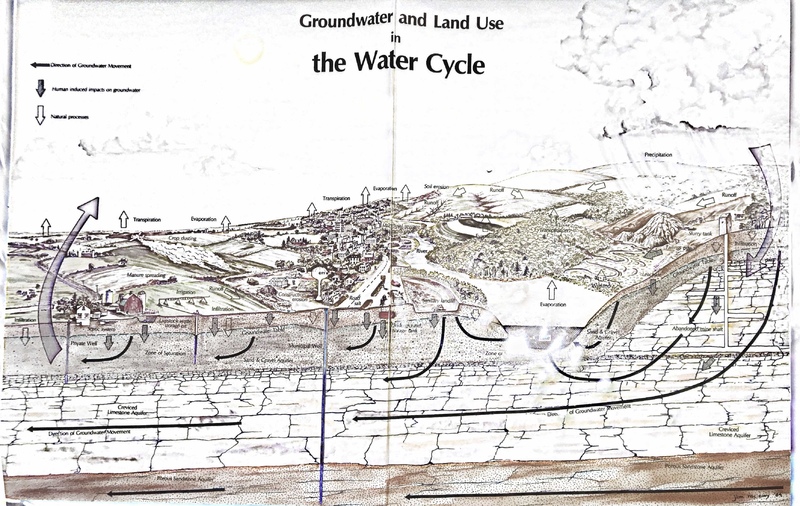

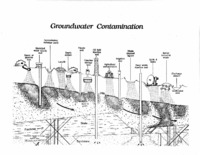

As the diagrams at right and below show, precipitation enters the ground and flows through soil until it reaches the water table, or aquifer. Groundwater flows through aquifers from higher ground (entry point) to lower ground (discharge areas) where it releases into rivers/lakes. Contaminants enter the same way as precipitation, but can have toxic effects on the water supply. Contaminants lighter than water do not dissolve, but instead float on the water table underground. Contaminants that dissolve travel the same routes as the water itself. Contaminants heavier than water sink to the bottom of the aquifer, where they can poison the water supply slowly over time. Educating students about the dynamics of the water cycle highlighted that pollution could take multiple forms.

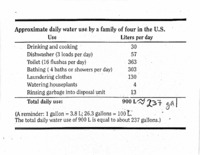

Hands-on activities were also popular in the classroom as a way of educating students not just about groundwater, but also about water consumption more broadly. One game called “Bucket Brigade” created an assembly line of students carrying buckets of water from one location to another. This activity helped students visualize how much water is consumed per day by a four-person family.

Another interactive project taught middle-schoolers about the role of water purification plants and explained government standards for clean water. This module also taught students about natural methods for water purification through filtration, aeration, settling, and freezing cycles.

Groundwater Education on Wheels’ purpose is “to heighten student and youth awareness of the groundwater resource and of groundwater protection strategies.” - Michael Garfield, lead author, GEE-WOW! Request for Funding

GEE-WOW! Grant Proposal

The Ecology Center’s various groundwater education initiatives would soon consolidate into Groundwater Education on Wheels, or GEE-WOW! This program became the EC’s defining education initiative in the 1990s.

GEE-WOW! was officially proposed on December 7, 1988 in a grant application to the W.K. Kellogg Foundation and its affiliated Groundwater Education in Michigan program. The proposal requested a three-year grant, totaling $186,000, to support widespread groundwater education projects. While GEE-WOW! would be officially operated by the Ecology Center, the proposal anticipated collaborations with Eastern Michigan University, the Washtenaw County Hazardous Substances Panel, the Michigan Sea Grant, the U-M Biological Station See North Program, and the Community Foundation for Southeast Michigan.

The proposal identified four specific goals:

-

Create permanent, ongoing education programs that were hands-on for children

-

Assess public school curricula to see where information about groundwater could be included

-

Produce and distribute groundwater education materials

-

Encourage similar projects in other states

The Kellogg Foundation grant was approved on March 1, 1989, providing the Ecology Center with crucial funding for what would come to be a flagship educational initiative throughout the 1990s.

In many ways, Ward’s grant proposal reflected Stapp’s student-centered, action oriented vision for environmental education. One of the sample activities in the proposal called on students to “concoct a ‘landfill pollution’ problem by filling a miniature perforated trash can with solid waste and food coloring….[and] track[ing] and graph[ing] the pollution plume.” By providing students with these hands-on opportunities, centered around real community problems, Ward explained that she hoped to “empower young students to be able to change what’s around them.”

The proposed programming would also meet students where they were at, both literally and figuratively. Equipped with a donated station wagon, Ward and her Ecology Center colleague, Ruth Kraut, traveled around the seven-county region in southeast Michigan to present to children in their schools, their Scout meetings, their 4-H groups, or anywhere else they could be found. Rebecca Kanner and Claire Pferdner also played a major role in the Center’s environmental education programming at the time. Pferdner had a background in museum exhibit design and conceived much of the assembly material.

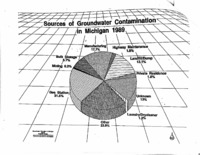

The choice of groundwater as a focus was a clear choice for the Ecology Center. Groundwater contamination was a major concern for both the organization and the state of Michigan in the 1980s and 1990s. In 1986, the Ecology Center joined a high-profile battle for the cleanup of Gelman Sciences, a medical filter manufacturer that was responsible for a 1,4 dioxane plume that had started to form as early as the 1960s. But the Gelman leak was far from the only groundwater concern in the state. In introducing the GEE-WOW!’s K-6 activity guide, Ward began her letter to the educator with the alarming statistic that, “In February of 1990, the Michigan Department of Natural Resources identified 2,662 sites of soil and groundwater contamination in the state of Michigan alone”.

The focus on groundwater also presented a unique pedagogical challenge. As Ward explained in a 2019 interview, groundwater flows in the porous rocks beneath our feet, much of it unseen. As a result, students and adults alike hold misconceptions about what groundwater is and how they can impact it. Adding to this complexity is the fact that many kinds of activities can contaminate groundwater, such as improperly disposing of household cleaners and fertilizing lawns. Therefore, one of the key challenges of GEE-WOW! was to make groundwater issues tangible and accessible to students without oversimplifying the complex systems involved.