See a related article from the Ecology Center's website, Return to Returnables: Michigan’s 1976 Bottle Bill

Michigan Bottle Bill of 1976

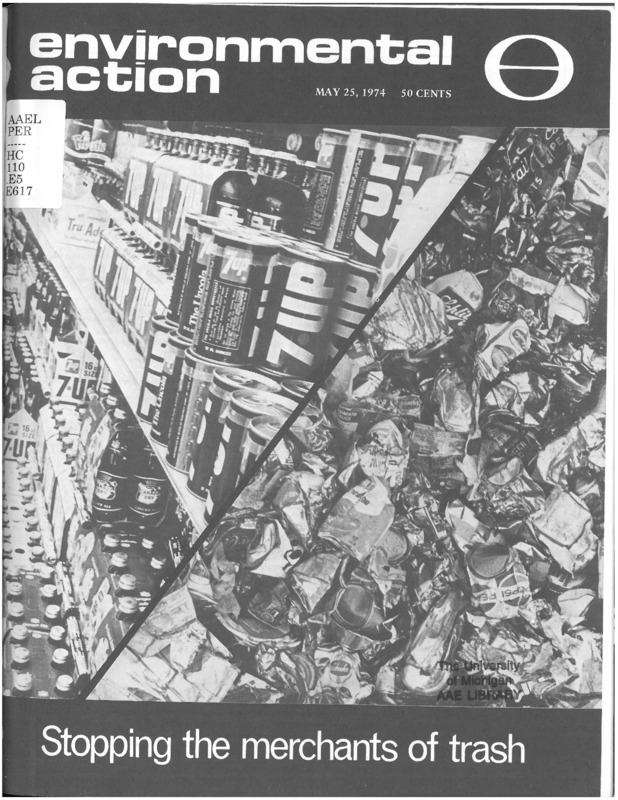

In the early 1970s, throwaway bottles and cans composed 80% of Michigan’s roadside litter. Environmental groups like the Ecology Center hoped to protect Michigan's natural beauty by advocating for a return to returnable containers to change the “throwaway mentality” that dominated American culture. In 1971, the Oregon legislature passed the nation’s first “bottle bill” which placed a five-cent deposit on returnable beer and soft drink containers. This incentive was designed to benefit the environment by decreasing litter and reducing energy consumption. Vermont followed in 1972, and many hoped Michigan would be next. It seemed likely, considering that in 1970 its legislature passed the landmark Michigan Environmental Protection Act and Governor William Milliken publicly stated his support for a ban on non-returnable bottles. However, none of the bottle bills proposed to the legislature in the early 1970s made it out of committee as a result of the opposition from retailers, labor groups, and the bottling industry.

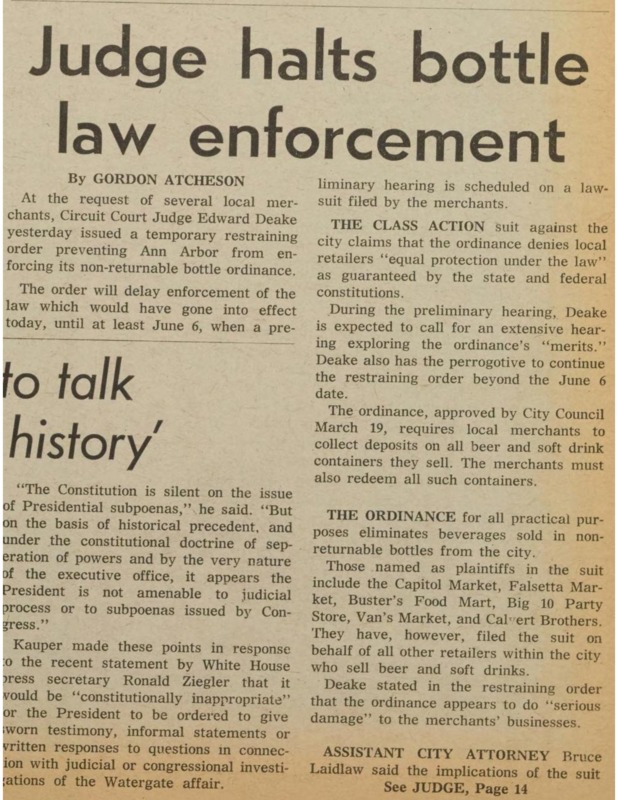

When the state failed to act, local communities proposed their own ordinances banning throwaway beverage containers, often led by environmental organizations like the Ecology Center. Although it was ultimately unsuccessful, the Ecology Center’s 1973 ordinance would have created the first local returnable bottle deposit system in the state. The Ann Arbor community’s support for the ordinance showed that economic fears sown by the bottling industry could be overcome with citizen education and a careful presentation of the facts. After retailers filed a lawsuit against the city, the Circuit Court judge ruled against the ordinance on the grounds that it would conflict with the state’s authority to regulate liquor packaging and sales. Because of this, it was clear that a deposit system for returnable bottles could only be created at the state level.

Turning to statewide solutions, the staff of the Ecology Center used their experiences to advocate for returnable beverage container legislation. In 1975, Representative Lynn Jondahl re-introduced House Bill 4296, a bill that would require a minimum ten-cent deposit on all containers of beer and soft drinks and ban pull-tabs on containers sold in Michigan. In April, Tom Blessing, who would later become Assistant Director of the Ecology Center, spoke “in strong support of H.B. 4296” before the House Consumers Committee. He described the bill as “the only real answer to resource conservation available for the beverage packing industry.” Because the Ecology Center operated one of the largest community recycling programs in the state, he spoke with authority about how the law would decrease litter and ease the burden on waste disposal centers across the state. Governor Milliken also appointed Blessing to the Michigan Resource Recovery Commission, an organization that advised the Department of Natural Resources on solid waste policy. There, he urged the Commission to recommend returnable beverage container legislation.

In November 1975, instead of sending H.B. 4296 to the floor of the House for a vote, the House Consumers Committee sent it to the Appropriations Committee, where environmentalists believed it would be defeated once again. Tom Washington, head of the Michigan United Conservation Clubs (MUCC), announced that his organization would launch a campaign to place the issue in the hands of Michigan voters. To place the bottle bill on the November 1976 ballot, the MUCC and its allies would need to circulate petitions and collect 212,000 signatures by June. It would be a challenge because, according to conservationist and historian Dave Dempsey, “no conservation measure had ever reached the ballot this way.” But the MUCC felt the campaign would be successful: a statewide study conducted in late 1975 showed that 73.3% of Michigan citizens supported returnable bottle legislation.

Michigan’s grassroots network of environmental organizations went to work. In Ann Arbor, the Ecology Center helped found the Return to Returnables Committee, the Michigan Returnables Coalition, and the Washtenaw County branch of Help Abolish Throwaways to support the initiative by circulating petitions. Through its community education programs, the Center emphasized environmental arguments in favor of the bottle bill and encouraged citizens to learn more about the issue from the materials in its environmental library. Through its monthly newsletters, the Ecology Center kept readers up to date with the petition drive’s progress. In this letter to the Ann Arbor News, the Center’s Board of Directors invited readers to pick up blank petitions at its headquarters so they could collect signatures themselves.

By June 1, volunteers in communities throughout the state had collected over 400,000 signatures in favor of placing the issue on the ballot. After overcoming this obstacle, the coalition renewed its efforts to convince Michiganders to vote in favor of Proposal A, the bottle bill, on November 2, 1976.

Though public support was overwhelmingly with the environmentalists, they were fighting the more-powerful and better-funded bottling industry. It, along with several labor unions and retailers’ associations, mounted a $1.3 million advertising campaign opposing Proposal A, arguing that it would burden retailers with extra work and drive industry from Michigan, resulting in job loss.

In Washtenaw County, the Help Abolish Throwaways Committee staged a protest to dramatize the problem. On October 11, volunteers collected throwaway bottles and cans strewn along a 10 mile stretch of the Huron River. Catherine Anderson, one of the group's leaders, told the Detroit Free Press that the 37,000 containers they had collected created a mountain "higher than my head and I'm almost six feet tall." As election day neared, anti-bottle bill advertisements filled the radio and newspapers, but the environmentalists persisted. Ann Arbor groups held a rally on the University of Michigan Diag two weeks before the election. They also refuted their opponents' claims by circulating pamphlets like this one:

"WILL IT COST MICHIGAN JOBS?

No! It will generate 4,000 - 8,000 new jobs in the state in trucking, warehousing, and retailing.

WILL IT SAVE ENERGY?

Yes! We will save enough energy here to heat every home in Grand Rapids.

WHY IS THE BEVERAGE AND CONTAINER INDUSTRY GOING TO SPEND $3.5 MILLION TO DEFEAT PROPOSAL A?

Because they make money with throwaways. You pay for the container and then you pay taxes to clean up the mess."

On November 2, 1976, 64% of Michiganders—and 76% of Washtenaw County voters—approved Proposal A, endorsing a return to returnables. Implemented on December 3, 1978, the Beverage Container Act made Michigan the third state in the United States to establish a mandatory deposit system for returnable beer and soft drink containers and the first to ban pull-tabs on metal cans.

After their victory, bottle bill advocates supervised its implementation in Michigan while supporting bottle bills being considered in other states and at the national level. In 1978, Dave Lynch, the Ecology Center’s newsletter editor, testified before a Michigan House special committee and provided advice about conducting an impact study. The details mattered, he said, because “throwaway ban opponents and proponents will be closely watching Michigan, seeking information to use in the battle over national legislation.” Later that year, Lynch testified before the US House Subcommittee on Transportation and Commerce. Speaking in favor of H.R. 7155, a nationwide bottle bill, he pointed to preliminary studies about the impact of the Michigan Bottle Bill to make the case for a national mandatory bottle deposit law. Four years after Michigan’s law went into effect, a study revealed that it had reduced litter by 40% and annually saved 15,000 tons of aluminum and 65,000 tons of glass. Despite similarly positive results in each state with a returnable bottle law, no national law has ever been passed.

To this day, Michigan’s ten-cent deposit is the highest in the country and as a result, its redemption rate is the highest too, at 94.2% in 2014. Everyone who lives in Michigan has this coalition of environmental organizations to thank for the immense reduction in roadside litter the state has seen since the 1970s. Over the course of nearly a decade, the Ecology Center pursued the issue in Ann Arbor and used what it learned from its failures to push statewide legislation forward. Joined by a coalition of Michigan environmentalists, they took an idea and turned it into policy, changing the culture and helping the environment in the process.