Pesticide Task Force

"Should neighbors be warned when pesticides will be sprayed next door? To what are small children exposed when lawns are sprayed? What are the dangers in home use of available pesticides? Are there effective alternative methods? Is there any inspection program to insure that food is free of pesticide residues? We plan to research these questions..." -Notes from the Pesticide Task Force, November 26, 1985

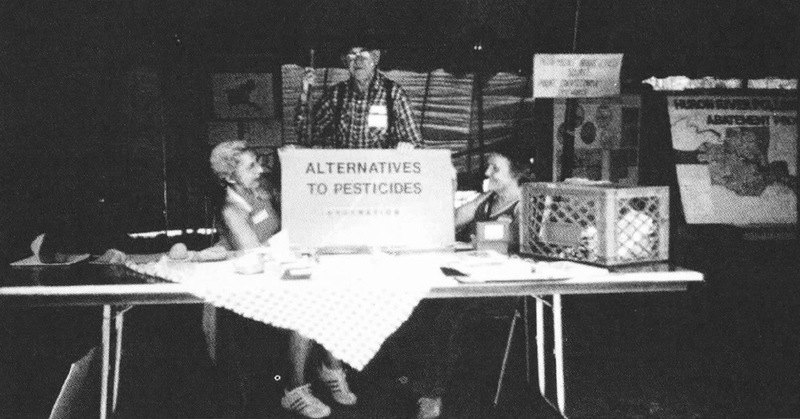

Growing out of concern about the negative impact of pesticide use on public and environmental health, in 1985 a volunteer-based group of interested citizens affiliated with the Ecology Center in order to research pesticide use and management in Washtenaw County. Called the Pesticide Task Force (PTF), the group met frequently to discuss how to mitigate threats posed by pesticides. These strategies included encouraging management plans that reduced pesticide use, proposing alternatives to chemical treatments, and providing support to those negatively impacted by spray programs. Initially, the PTF focused on developing strategies and educational materials related to pesticide use by individuals. In following years, the group's agenda expanded from educating users to organizing and lobbying on a larger scale.

A Push for Organic Produce

A series of scientific studies in the early 1980s warned that pesticide residues, many of which the EPA identified as possible carcinogens, coated much of the produce available in grocery stores across the country. The Michigan Department of Agriculture (MDA) doubted these claims, instead asserting that pesticides posed "no threat to the state's population or environment." Many Michiganders, however, remained unconvinced.

In 1988, the Pesticide Task Force began a year-long campaign urging local grocery stores to stock organic produce. Although supermarket representatives agreed to consider the suggestion, they remained skeptical about consumers' willingness to purchase organic foods which were typically more expensive and less visually appealing than those grown with pesticides. In response to corporate hesitation, the PTF conducted a survey at three Kroger stores. In five hours the group collected 524 signatures supporting the inclusion of organic produce.

In February 1989, six Ann Arbor Kroger locations opened "certified organic" produce sections. These sold fruits and vegetables grown without synthetic pesticides, fertilizers, or growth regulators. Marked with green and white signs, shoppers could choose from citrus, apples, potatoes, lettuce, and other vegetables. This move made Kroger the first local supermarket chain to have an organic food section. The company's decision set an example for other supermarkets in the area.

Working with Ann Arbor Public Schools towards Integrated Pest Management Program

"A school system that in theory teaches our children to be good citizens of this planet and then in practice spreads poisons on their playing fields must re-examine its policies and priorities and show ecological, moral, and fiscal responsibility." - Letter from concerned AAPS parent, June 1988

During the summer of 1988, the Ann Arbor Public Schools (AAPS) undertook an $11,000 contract with TruGreen Corporation to manage dandelions and other weeds on district properties. On a warm and windy day in the early summer, spray drift from a herbicide application sparked what a reporter from the Ann Arbor News referred to as the "War of the Dandelions." In the weeks that followed, complaints poured in from angry parents who feared for the health of their children and from nearby residents whose lawns and gardens had been damaged by the sprays.

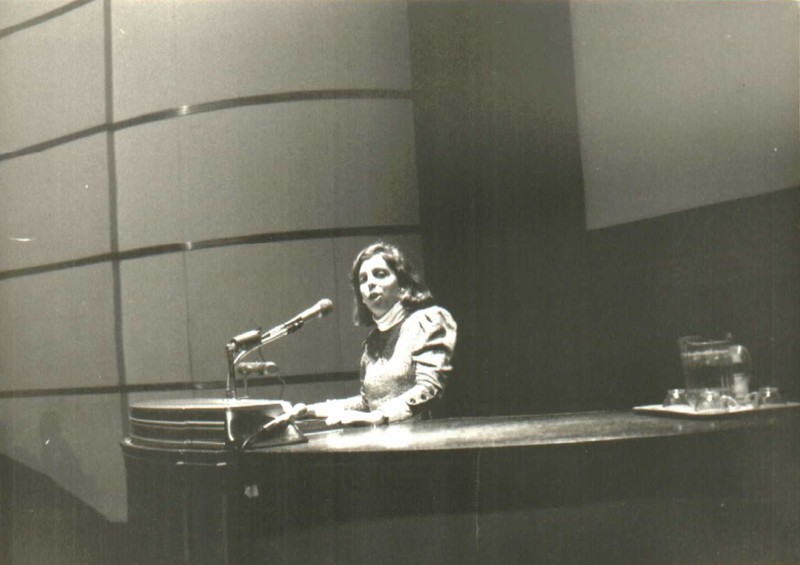

To hear from all sides, the AAPS facilities director met with TruGreen representatives, school officials, concerned parents, and Ecology Center representatives in June 1988. Over the next eighteen months, members of the schools' facility management staff worked with the Ecology Center to revise the district's pesticide policies with an eye to reducing the use of synthetic pesticides. Richard Benjamin, the district superintendent, remarked that working with the Ecology Center "brought to our attention a wide variety of problems" regarding how the AAPS undertook pest control. A new policy, formally adopted in December 1989, emphasized that if pesticides or herbicides were sprayed, it must be because there was the threat of an "impending loss of the aesthetic, structural or functional integrity of an important district resource which cannot be managed without the use of pesticides" and that parents and staff must be notified of any such application. The adoption of this policy represented a remarkable improvement from the unconstrained and unannounced dandelion sprays of the previous summer and demonstrated that the Ecology Center could successfully advocate for the community.

Providing Reporting System for Pesticide Spray Exposure Victims

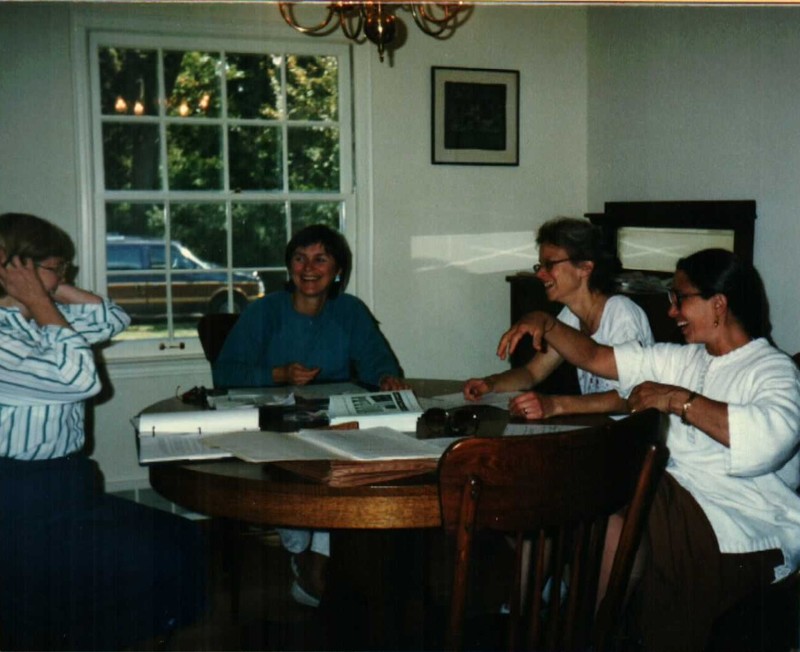

In 1989, the Pesticide Task Force teamed up with four other citizen organizations involved with pesticide issues - the League of Women Voters in Michigan, the Clean Water Action Project of Lansing, the West Michigan Environmental Action Council, and Citizens against Chemical Contamination - to form the Michigan Pesticide Network (MPN). Covering most of the state, the MPN collaborated to design and implement a voluntary reporting system gathering data on pesticide exposure incidents. Although the Ecology Center staff had already begun an initiative to track and reporting adverse pesticide effects, this represented the first formal and statewide effort to consolidate such reports into a more coherent and expansive body of evidence.

To gauge the extent of exposure, the MPN set up seven regional hotline numbers which pesticide spray victims or their families and friends could report an incident and receive support. Hotline staff could provide callers with receive physician referrals and incident reporting forms to jot down necessary information for medical and legal purposes. Pesticide exposure victims frequently suffered from a strange and diverse range of symptoms, so a formal reporting mechanism allowed the various responses to pesticide sprays to be systematically recorded and subsequently shared with medical professionals where such information could support diagnosis and treatment.