See a related article from the Ecology Center's website, Playing the Long Game: How Detroiters Finally Won the 30 Year Fight to Shut Down Enormous Trash Incinerator

Taking on Incinerators to Fight Toxins

The Ecology Center’s efforts to fight waste incinerators throughout the 2000s was a continuation of their advocacy work and commitment to the coalition-building they had done the previous two decades. An alternative to landfills, waste incinerators, especially those that burn medical waste, are notorious sources of air pollution. When waste is burned, toxins like dioxin, lead and even mercury are released. This can happen when chemicals found in products, like mercury car switches, are introduced to the air or when burning substances like chlorine produce new toxins like dioxin. Dioxin is actually a group of 75 carcinogenic chemicals all of which can also lead to developmental problems and birth defects.

Shutting Down Michigan's Last Medical Incinerators

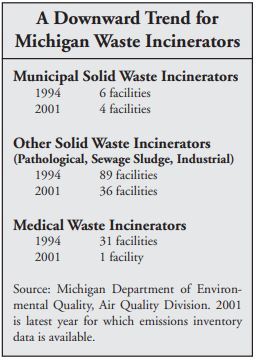

Central to the Ecology Center’s advocacy work to shut down all 157 of Michigan’s medical incinerators was coalition building and rallying public support for the cause. Partly in response to new federal emissions regulations, the University of Michigan’s Medical Center shut down its medical waste incinerator in 2000 after fourteen years of operating and switched to autoclaving. Rather than incinerate medical waste, autoclaving allows for non-hazardous medical waste to be sterilized via rotating steam chambers before being shredded and stored in landfills. Combined with recycling initiatives, the Medical Center could cut down on toxic emissions and reduce waste.

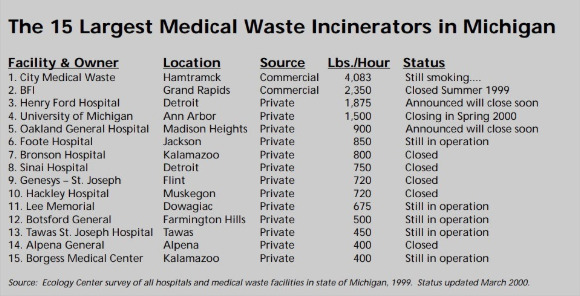

Throughout the state, the desire to see medical incinerators be replaced with safer alternatives only caught traction. The Ecology Center joined a coalition of environmentalists and community groups to protest the Henry Ford Health System Incinerator located in Detroit and advocate for its closure. Much like other medical incinerators this one was located in a predominantly low-income city with a high minority demographic, a textbook example of environmental racism. Throughout the late 90s the coalition sent letters, made phone calls to executives, and organized protests near the facility. At one point, activists even mounted a “stop smoking” banner across the street from the hospital where it sat for over two months. Fortunately, relief came early in 2000 when Henry Ford announced it would be closing the Detroit facility, though coalition members made sure to keep the pressure on the company until the toxic fumes had finally ceased.

By 2001, there was only one medical waste incinerator set to keep operating in Michigan. The incinerator, located in Hamtramck, had begun operations in the early 90s, but quickly began wracking up state regulation violations. Failure to control mercury emissions to inadequately training customers on waste delivery were just a few of the hundreds of violations. Hamtramck City Councilman, Rob Cedar, had advocated for shutting down the incinerator as early as 1996 and was head of the Hamtramck Environmental Action Team (HEAT) in the final operating years of the incinerator. This organization, along with the Ecology Center and the Sierra Club, led organizing efforts to shut down the incinerator for good. Meanwhile Norm Aardema, who purchased the site in 1999, attempted to jump on the bandwagon in the early 2000s and switched partially to autoclaving despite not having the proper clearance and doing so without remedying any of the incurred regulation violations. In 2003 Waste Management Systems (WMS), who operated the site, applied for an autoclaving permit from the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ).

Led by HEAT, coalition groups rallied for public support to deny the permits at the MDEQ’s public hearing to consider Aardema’s application. Ultimately the company’s requests from the MDEQ were denied based on the fact that WMS failed to “implement a mercury-waste reduction plan, to perform preventative maintenance activities and to provide complete records.” This denial meant WMS could neither incinerate medical waste nor autoclave it, effectively causing the facility to shut down in 2005 much to the benefit of the city.

The Long Fight Against Commercial Trash Incinerators

Unlike medical incinerators, commerical trash incinerators burn waste not limited to medical waste including municipal trash, car parts, and sewage sludge. Nevertheless they still spew toxic chemicals into the air, especially dioxin, which poses a significant risk to residents who live nearby. In fact, according to the U.S. EPA’s Dioxin Reassessment, in the early 2000s sewage sludge incinerators were the nation’s 13th leading source of dioxin into the environment

In Oakland County, the aluminum smelter there had direct health impacts, causing a range of illnesses in local residents from asthma to cancer. In March of 2000 the MDEQ cited Continental Aluminum, the owners of the incinerator, for air pollution violations, but when the Ecology Center reviewed the companies submittals they found the MDEQ had failed to adequately review Continental's initial proposal for site operations some seven years prior. The Ecology Center discovered the control equipment on site was never actually properly engineered for the facility. Revelations like these were unsurprising to Lyon Township residents who had filed hundreds of odor complaints and staged rallies at the plant to raise awareness. In response to this form of environmental injustice, the Ecology Center centered their opposition around alternatives to the problem of incinerators. They urged automakers to make cars more recyclable and reduce the use of toxic components, like mercury and PVC plastics, in order to reduce toxic incinerator emissions. In addition, they joined residents in advocating for stricter air quality standards for aluminum smelters.

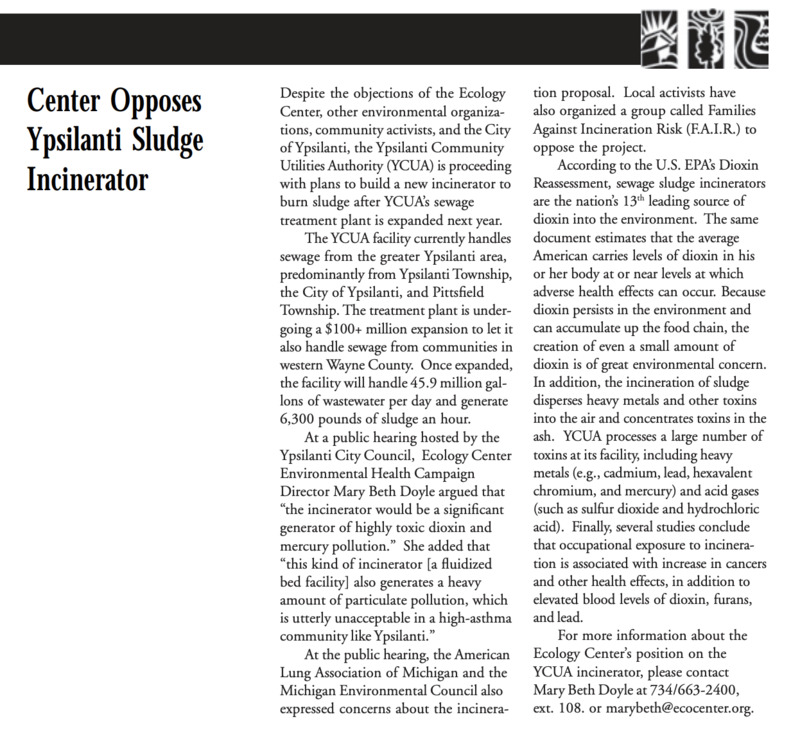

In other parts of Michigan, the Ecology Center sought more preemptive measures and such as joining community activists and the city of Ypsilanti to publicly object to the Ypsilanti Community Utilities Authority (YCUA)’s plans to construct a new sewage sludge incinerator. At the time in 2000, the plant was undergoing a $100 million expansion in order to accommodate waste from surrounding areas and once expanded, would be able to handle 45.9 million gallons of wastewater a day and generate 6,300 pounds of sludge in an hour. Not only would it produce high levels of mercury and dioxin, but the proposed incinerator was a “fluidized bed facility,” which meant it generated a heavy amount of particulate pollution and released heavy metals that concentrated into leftover ash. At a public hearing hosted by the Ypsilanti City Council, Mary Beth Doyle of the Ecology Center noted at the time that the proposed incinerator’s high mercury and dioxin emissions posed a high significant risk to residents, especially as Ypsilanti was already a high-asthma community. Deeply concerned, local activists formed Families Against Incinerator Risk to stop the incinerator, but regardless the YCUA was approved to move forward with the expansion.

In Dundee, the Ecology Center along with environmentalists and local residents announced their plans in late 2001 to oppose the expansion of Michigan's 6th largest polluter, the Holcim cement incinerator. The expansion permit that Holcim applied for would’ve allowed the incinerator to burn an additional 80 different kinds of waste. While none of the waste materials they wanted to burn were regulated as hazardous, a number of them contained toxic contaminants such as auto fluff, which is contaminated with PVC, lead, and mercury. In addition, even before the expansion Holcim had failed to reduce toxin and greenhouse emissions by continuing to use a wet process of cement formation, which used >50% more fuel than the up to date dry and semi-dry processes. When requesting a permit, Holcim’s lawyers also argued that most of the plant’s operation should be grandfathered from the original state review, which would've allowed Holcim to continue producing toxins that had since been restricted. At the time, a Holcim representative even stated in a letter to the DEQ that, “It is entirely possible that a source the size of the kilns would have pre-existing emissions of some toxic air contaminants that would not be able to meet the standards imposed on new sources under the air toxics rules.” In 2003, the MDEQ granted Holcim Cement plant the permits to expand. Just as in Lyon Township, the Ecology Center and Citizens Against Polluting the Environment (CAPE) acknowledged that the struggle against incinerators would be a long one and oriented their efforts on ways to at the very least minimize the damage. Two main ways were to urge Holcim to switch to dry processing and ideally quarry their limestone (which is needed to make cement) elsewhere, as it was the main source of emissions.

While strong odors might be the strongest signifiers of incinerators, they are also shining examples of environmental injustice and racism. Placing incinerators in low-income communities and communities of color had become common practice, which the Ecology Center and other activist groups sought to point out in the 2000s. In Detroit, the Greater Detroit Resource Recovery Authority and Covanta Energy Corporation-operated municipal trash incinerator became a target for a coalition of environmental groups including the Ecology Center, Detroiters Working for Environmental Justice, and 10 other community organizers. The incinerator was actually owned by Philip Morris Capital Corporation, a subsidiary of the tobacco conglomerate, which bought the incinerator in 1991 and leased it back to the city. Donele Wilkins of Detroiters Working for Environmental Justice noted:

"It's been well-documented that cigarette companies target minority communities like Detroit with their billboards. It’s ironic Philip Morris is targeting our community with the country’s largest municipal waste incinerator as well."

According to the Ecology Center’s Mary Beth Doyle, “the incinerator sits in the heart of the city where I-75 and I-94 intersect, in a low-income, predominantly African American neighborhood. The surrounding community is already exposed to pollutants from numerous sources in the area, including Michigan’s only commercial medical waste incinerator [Henry Ford Hospital], the GM Poletown plant, and two major highways.” Doyle drew a correlation between the presence of these sources of pollution and poor health in the community, including disproportionate rates of elevated blood lead levels and asthma. An AP analysis later found that African Americans were at the time 79 percent more likely to live in neighborhoods where industrial pollution posed the greatest health risk.

While the risk might have been worth some financial reward, in actuality, the continued operation of the incinerator was an economic disaster for Detroit; the city spent $77 million to burn and landfill approximately 600,000 tons of trash. At the same time, the $130-per-ton cost was outlandishly expensive, since the disposal costs paid by its suburban neighbors were far less, with Southern Oakland County paying $14/ton, and Ann Arbor paying even less for their combined program of recycling, composting, and landfill disposal. In 2002 the environmental groups urged Mayor Kilpatrick to shut down the incinerator for a “clean and safe Detroit.” Their proposed solution was to stop incinerating trash and enact a comprehensive recycling program in the city, arguing that it was a matter of environmental justice, public health, and the most cost-effective choice. In the meantime, activists had also hoped the MDEQ might deny the incinerator a Renewable Operating Permit, which allowed the incinerator to be deemed a renewable source of energy because the steam produced could generate electricity elsewhere.

Elsewhere in Wayne County, the Central Wayne Sanitation Authority (CWSA) had reopened the expanded Central Wayne Trash Incinerator, releasing 400lbs of toxic ash per every ton of waste burned. Having underestimated the amount of toxic ash being produced by the incinerator, which contained PCBS, cadmium, mercury, and even lead, the Authority applied for a bond to build a fourth cell in 2003 to accommodate their growing landfill of ash. Their water permit had also allowed them to discharge treated leachate directly into the Huron River. In response, the Ecology Center and Clean Water Action supported an outreach campaign in Westland which produced 400 letters all written to the city mayor and city council encouraging them to shut down the incinerator and instead implement a comprehensive recycling curbside-recycling plan. In the same year, residents living near the landfills also created the REACT program (Residents Enraged Against Canadian & Out-of-state Trash) to voice their concerns about the presence of extremely large trash trucks in their area. Then to the surprise of activists the Central Wayne Trash Incinerator abruptly closed in 2003 after the Central Wayne Energy Recovery Limited Plan (CWERLP) defaulted on the bonds issued to them by the Michigan Strategic Fund (MSF). Ironically, the CWERLP had failed to profitably operate the incinerator because landfills prices were so low.

In light of this, Ecology Center representatives suggested to the shareholders to convert the facility to a garbage transfer station and materials recovery facility, but the CWSA announced that the Dearborn Heights incinerator facility would be permanently closed on Earth Day, 2004. The CWCSA borrowed $8 million from Waste Management Michigan in order to leave it’s 35-year contract with CWERLP, who operated the facility. CWCSA’s new 20-year repayment plan to WMM increased their landfill dumping fee from $13 per ton to $20. Though the landfill fee increased, shutting down the incinerator would save CWCSA $50 million over the 20-year period. Using the saved money, the Ecology Center supported the creation of a recycling program though no initiatives were taken.

With mixed results, the Ecology Center nonetheless continued its campaign to shut down all incinerators in Michigan optimistic as the business appeared to be in decline considering the economic burden of operating costs and its inability to compete with cheaper waste options like landfills. To emphasize the severity of the situation, in early 2006 the Ecology Center in collaboration with others created a website where users could look up their Industrial Air Pollution Health Risk Score. According to the data, a score of 19.5 was considered among the worst 5 percent in the country. Saint Aubin St., about four blocks east of Detroit incinerator scored 31.6 while Georgia St., about two blocks east of Hamtramck Medical Waste Incinerator, was 40.4. In addition, the organization joined over 40 others as part of the Campaign for State Action on Environmental Justice in writing a letter for the Environmental Action Advisory Council of MDEQ urging Governor Granholm to adopt policies through executive action that would support environmental justice measures.

Back in Detroit, the Ecology Center continued to seek change. They promoted public rallies calling for the closure and replacement of the Detroit Incinerator and in 2008, joined nine other environmental, civic, and recycling groups to officially create the New Business Model for Detroit Solid Waste Coalition, which pushed for the city government to end incineration altogether. The New Business Model for Solid Waste measure was adopted by the Detroit City Council in April of that year and enabled the city to lower waste disposal costs by recovering materials through recycling/reuse, reduce waste sent to landfills, and end the city’s dependence on incineration entirely. Newly elected leadership would have the option to move away from incineration after July 1st, 2009, as the city’s 20-year bond debt to build and upgrade the incinerator was to be completely repaid at that time. Much to the outrage of citizens though, despite the fact that the newly elected Mayor Bing stated during his campaign that he supported the New Business Model for Detroit Solid Waste, on May 26 the City Council reversed its decision and voted against the economic development plan. In the Take Action section of their newsletter, the Ecology Center urged its supporters to contact Mayor Bing’s office and hold him to his campaign promise: “What you burn you cannot earn.” They asked that readers “tell Mayor Bing, his chief operating officer, and the Detroit City Council to halt delivery of Detroit’s trash to the incinerator” as well as demand the mayor take these major steps:

- Stop burning trash at the Detroit incinerator.

- Act on behalf of Detroit residents and not the waste industry.

- Increase curbside recycling to create more jobs and make Detroit a healthier city.

Though the city was “on the cusp of recycling” considering the contract for the incinerator was up, city officials ultimately extended the contract on a monthly basis on June 30, 2009, leaving citizens and activists continuously guessing at the city’s long-term plans. Although trash incinerators continued to be operational well into the next decade, the work of the Ecology Center and the numerous coalitions they joined made significant progress towards raising awareness, promoting recycling and alternatives to incinerators, and ultimately enabling communities to better fight for health and justice in their own neighborhoods.

Coal Plants and Clean Energy Now

In 2009, the Ecology Center helped form Clean Energy Now, a coalition of over 40 organizations. The coalition focused their efforts on preventing the building of new coal plants in the state (at which time there were eight being proposed) and promoting the use of alternatives. The same year, Governor Granholm signed an Executive Order, dubbed a "moratorium on coal," to prioritize clean energy and require all new and expanded coal plant developers to go back to the drawing board and consider cleaner energy alternatives first. At the same time, Granholm also toughened existing coal pollution standards. Within months the developers of two plants – one at Northern Michigan University in Marquette and an LS Power plant in Midland – withdrew their permit applications.

In their "Take Action" section of their periodical newsletter, the Ecology Center asked readers to email in their concerns, stories, and photos of coal’s impact on them/their communities. Clean Energy Now compiled readers' input into a photo petition to MDEQ during a public hearing for a proposed Bay City plant owned by Consumers Energy in April of 2009. In advocating against new coal plants, the Ecology Center continued to inform their readers, notably reminding readers of four public comment periods open “regarding consideration of feasible and prudent alternatives to coal-fired power plants” as mandated by Granholm’s February 2009 Executive Directive. Soon after, Clean Energy Now members held a "Rally for Clean Energy Jobs" in Lansing where over 500 clean energy advocates rallied on the Capitol steps to advocate against building new coal plants and expanding existing ones. The Ecology Center and their allies continued their fight to halt the production and expansion of new coal plants well into the next decade.

Additional Sources:

"Burnt Out?" Detroit Metro Times, Nov. 28, 2001.

Carly Southworth, " 'U' Medical Center to meet new standards for medical incinerator," The Michigan Daily, (Ann Arbor, MI), Apr. 2, 1998.

Curt Guyette, "Raining Mercury," Detroit Metro Times, Sep. 22, 1999.

"Hamtown Hooray!" Detroit Metro Times, Jan. 26, 2005.

"Taking Out the Trash," Detroit Metro Times, Dec. 1, 2004.