The Fight Over Phase III: Ann Arbor’s Landfill Crisis

"The City of Ann Arbor is literally burying itself in garbage. The average Ann Arbor resident currently generates 2,200 pounds of garbage each year. City-wide, this translates into almost 250 million pounds of city-wide trash per year, enough to fill the University of Michigan Football Stadium at least twice…All of us have contributed to the problem, and all of us need to contribute to the solution.” -Ecology Center's proposed Waste Reduction and Recycling Ordinance, November 1988.

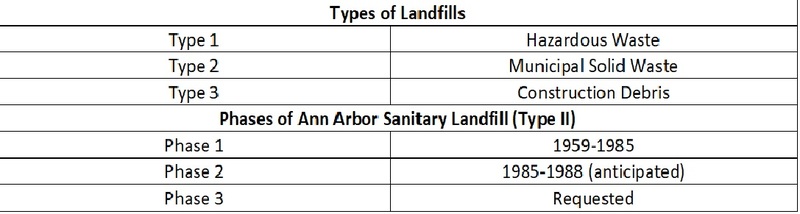

The City of Ann Arbor appeared to be heading in a positive direction for solid waste management by the end of the 1980s. As the deadline for closing Phase II of the Ann Arbor Landfill loomed in 1988, the city had approved the Ecology Center’s ordinance for mandatory recycling and was also in the process of removing compostables from the waste stream. Even as these measures redirected materials that would have previously been sent to landfill, as the above quote suggests the issue of sufficient space remained. Phase I of the landfill had met city needs from 1959-1985, but, due to Ann Arbor’s population growth in the 1980s, the city estimated Phase II only had enough space for three years with an anticipated closure in 1988.

Phase III, the next expansion of the city landfill, promised storage space for a minimum of 20 years. At its maximum, the city estimated the expansion could potentially last for 120 years if recycling and composting efforts continued to develop. Before going forward with Phase III, however, the city needed the approval of the Michigan Department of Natural Resources (DNR). That approval was far from guaranteed since the DNR was growing increasingly skeptical of the city’s ability to prevent its landfill from further contaminating an aquifer positioned just beneath the site.

A Track Record of Contamination

Part of the DNR’s skepticism over the Phase III proposal was due to the city of Ann Arbor’s uneven track record of preventing groundwater contamination and leakage at the landfill. When the city’s landfill was first founded in the 1940s, there was minimal oversight over what materials were dumped there. By the time the city officially took over the property in 1959, approximately two-thirds of the Phase I site was unlined. Without any kind of barrier waste lay in direct contact with the ground and could leach contaminants directly into the underground aquifer. The DNR made their approval of Phase III contingent on two counts: cleaning up existing groundwater contamination at the site and ensuring future contamination would not occur in the expansion.

To make matters worse, after Phase II had officially reached capacity illegal dumping continued at the site. According to an April, 1990 report in The Ann Arbor Observer, the excess waste - dubbed Mount Overfill - had resulted in a 60-foot-high rubbish pile, equivalent in size to a five-story building. Now, the city of Ann Arbor would not only need to prove to the DNR that they could clean up the groundwater contamination in Phase I; they would also need to explain why illegal dumping was now occurring, and determine where the excess waste could go.

To penalize the continued disposal, the DNR imposed a $108,000 fine on the city for the illegal dumping but allowed the waste to be moved to a new section of the landfill. Ecology Center director Mike Garfield, who was a member of the Ann Arbor Solid Waste Commission at the time, described the fine as a mere slap on the wrist. In July, 1990, shortly after the decision, he commented to The Ann Arbor News:

"I think you can make a case that the DNR did a real good job on this one...They get the work done, the environment doesn’t suffer for it, the city investigates the groundwater contamination, cleans it up, and the DNR whomps them with a fine that’s in accordance with what they said they would fine them.”

Mount Overfill would be settled with a simple fine. The Phase III proposal, however, would be a much more difficult problem to solve.

Phase III Fails to Meet DNR Standards

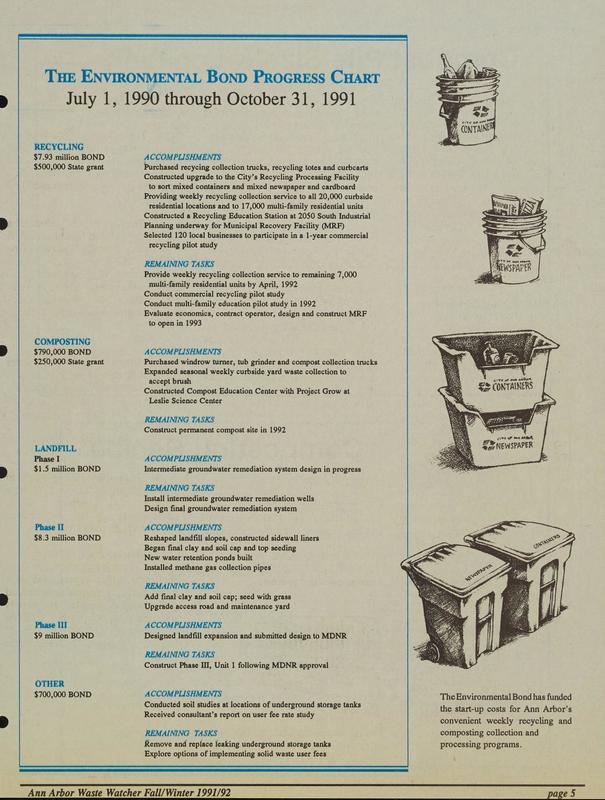

By the summer of 1991, the city’s application for Phase III appeared airtight. The new landfill space would have state-of-the-art landfill liners made of clay and rubber. Thanks to the 1990 Environmental Bond there was already $9 million available for the landfill’s first cell. Despite technical features and financial support, the landfill’s proximity to the aquifer remained a source of concern for the DNR. Though supported by U-M civil and environmental engineering professors, the DNR was skeptical of the landfill’s proposal to construct its base underneath the water table. Furthermore, the DNR claimed the city had not made good on its promises to clean up the groundwater contamination from Phase I, which, at this point, had been a known problem for nearly five years. On November 19, 1991, the DNR issued its final verdict: they did not grant the city of Ann Arbor permission to build the Phase III landfill.

Following this unexpected defeat, the city and its Solid Waste Commission weighed their options. They could sue the DNR for denying their permit and embroil themselves in a legal battle, they could redesign the Phase III landfill entirely, [r, they could abandon Phase III entirely and look into exporting their waste to a private landfill outside of Ann Arbor.

The Ecology Center supported this last option as the most cost-effective and environmentally sound plan. Financially, abandoning Phase III would save the city an estimated eighty-million dollars in construction costs. Transporting waste would represent a cost, but the new Materials Recovery Facility (MRF) was equipped to undertake haulage. Funded through the 1990 Environmental Bond, the MRF's initial purpose was to make the separation of recyclables more efficient and convenient. However, by building the MRF adjacent to the landfill, the facility could also serve as a temporary transfer station before sending the waste to a long-term disposal site.

After months of debate by city council, the Ecology Center’s recommendation prevailed. The MRF was slated to open in 1993 and, in the meantime, the city could divert its efforts and funding toward a more comprehensive cleanup of the contaminated groundwater.