Working with Community: Environmental Justice Coalitions

April 1990 marked the 20th anniversary of Earth Day. To commemorate the occasion, the Ecology Center coordinated a teach-in Groundswell ’90: Community Action to Save the Earth. At the event, David Stead, the director of the Michigan Environmental Council, spoke to the power collaboration had to weave together separate interests into a common cause. He called for “the environmental movement to initiate coalitions to address racism, unemployment, poverty, the homeless, education, peace and justice. (ER, 22.5, pg. 2)” By building ties with communities of color bearing a disproportionate share of pollutants, workers affected by toxics, and other environmental organizations, over the 1990s the EC engaged environmental harm as not only a serious environmental threat but also a deeply social concern.

Community Right-to-Know

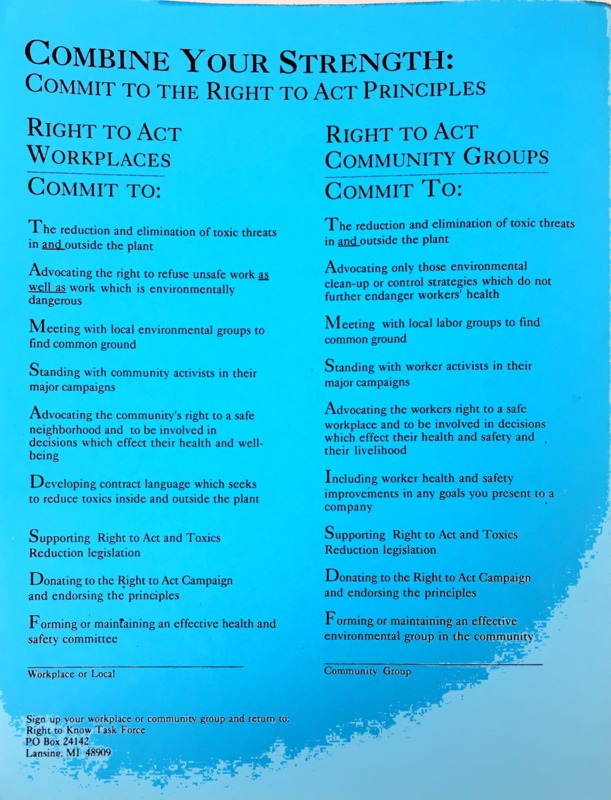

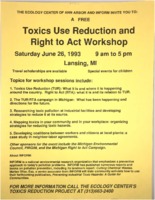

An After Earth Day Environmental Agenda released in Lansing in connection with the anniversary included enthusiasm for “community right-to-know.” This federal legislation, titled the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act, was passed in 1986 after the Union Carbide disaster in Bhopal, India. It required polluters to release information about harmful emissions in their communities. While an important step, uncertainty about what communities could do with that information inspired statewide conference in August 1990. Organized around the motto “from right-to-know to right-to-act” the gathering’s goal was to “empower workers and community members to organize for a safe and healthy workplace and environment. (ER, 22.10, pg. 6)” If knowing about pollution was the first step, then action to mitigate pollution’s impact on a community was the second.

Transparency and access to information was a particularly urgent concern in the early 1990s. In January 1992, environmental groups like the Sierra Club and the East Michigan Environmental Action Council joined the Ecology Center to protest Governor John Engler’s executive orders eliminating guaranteed citizen involvement in environmental decision-making. The coalition achieved a court resolution halting the orders.

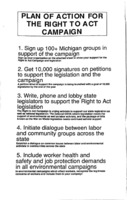

Later that year, the EC’s work promoting community involvement in environmental decision-making and right-to-act legislation switched from protection to legislative action. Arguing that “Michigan’s citizens – both in their communities and workplaces – [were] under assault from toxic hazards (ER, 24.6, pg. 1)” the EC supported state-level legislation (Senate Bill 1068) mandating reduction planning for toxics. In supporting the capacity of communities to contribute to environmental permitting, preserving the ability of citizens and workers to access information, and advocating toxics reduction the EC joined the Utility Workers union, the Michigan Environmental Council, and other community organizations.

The Ypsilanti Pollution Prevention Project

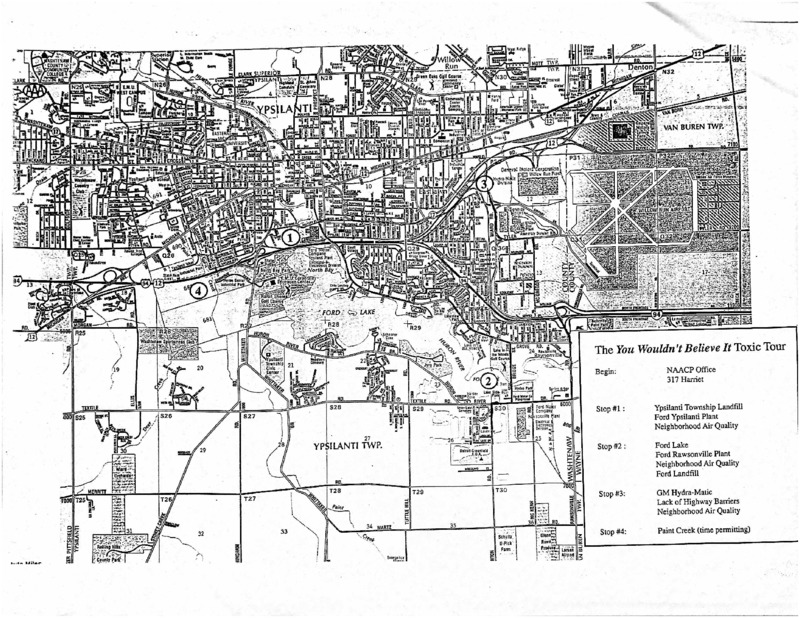

As it organized on a state-wide level the Ecology Center also developed collaborations with local communities. In October 1994, the EC joined the Ypsilanti/Willow Run branch of the NAACP to address impacts of pollution in eastern Washtenaw county. Ypsilanti was the county’s most industrialized community, had the highest percentage of people of color, and the lowest per capita income. These statistics demonstrated the preponderance of environmental hazards in low income and minority communities.

EC-NAACP collaboration took shape as the Ypsilanti Pollution Prevention Project (YP3). The YP3 sought to address environmental inequalities by stimulating community awareness and action on toxic issues, identifying community pollution prevention priorities, and providing technical support as needed. At a meeting in February 1995, one community member said “We must focus on how pollution affects us[.] (ER, 27.1, pg. 4)” Other aspects of the program included community meetings. A “You Wouldn’t Believe It” toxic tour to introduce residents to environmental concerns, and assisting residents of Forrest Knoll (a Iow-income housing development) with an environmental assessment and cleanup of Paint Creek.

Outreach through schools provided further opportunities to engage students and educators about environmental issues. Some examples of YP3 projects in the classroom saw seventh graders at Edmonson Middle School learning about environmental racism, forms of pollution, and environmental law. Younger pupils at Kettering Elementary visited Lansing to talk with their Senator Alma Wheeler; those students also developed an odor survey to take home that would let them report on possible sources of air pollution in their own neighborhoods. Tara Ward touched on the goal of the EC in an article for Ecology Reports:

By working with students “the EC staff and their teachers hope to bring to them the sense they can make a difference in their environment, and … [by learning] about their influence on community decisions now, they will surely be more interested and active as adults. (ER, 27.2, pg. 6)”

The YP3 project reflected an understanding of environmental justice based on partnership with local communities, education about sources and impacts of pollution, and empowerment through action. Amidst the EC’s 25th anniversary celebrations in 1995, its newsletter highlighted programs like YP3 and the Building Success summer program for low-income youth as indicative of “new directions for the Ecology Center’s education and outreach programs [and that] the next 25 years should prove interesting. (ER, 27.4, pg. 12)”

Statewide Cooperation

The EC also cooperated with community groups throughout Michigan. In Lansing, where GM employed over 14,000 people, the EC supported concerned citizens in demands that the company’s request for a $421 million tax abatement be tied to a commitment to reduce air pollution. In Pontiac two groups presented claims that GM operations in the city violated principles of environmental responsibility, that the company illegally filled wetland, and had failed to reduce toxic emissions and chemical use at the plant. While the strategies in each location varied, each showed how community engagement could impact corporate decision making as it connected to environmental justice.

Toward the end of the decade, concerns about implementing state environmental guidelines took center stage in conversations about environmental justice. In 1997, a decision by a state district court ruled that Michigan’s environmental permitting process did not adequately protect public health. Nor, the court found, did regulations provide for adequate public participation. At the core of the matter was a dispute about how the EPA should implement Title VI guidelines relating to civil rights and the environment. EPA guidelines acknowledged that some (suburban, mostly white) residents received additional protections in environmental permitting; it was the EC’s position that urban dwellers needed parity. (FGU, 30.2, pg. 27)” To address inequalities in the state’s permitting process, the EC became a founding member of the Michigan Environmental Justice Coalition and worked to remedy inadequacies in the state’s permitting process that afforded stronger protections to white suburban communities.

In 1998, in an event referred to as the Motown Showdown, the EC hosted a rally in Detroit to discuss the implementation of EPA Title VI guidelines. The “showdown” reflected opposition from business groups active in southeast Michigan who saw further environmental regulation as a hindrance to economic development. The EC replied that globalization, rather than environmental justice, was the more potent threat to brownfield redevelopment. Economic prosperity did not have to, in the eyes of the EC, come at the expense of the environment.

Environmental justice formed “a historic social movement calling for improved public policy in a field of broad social concern” that featured filing complaints under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act, suing polluters and the state, and fundamentally “confront[ing] the traditional environmental organization and regulatory agencies’ exclusion of People of Color and their concerns from the environmental agenda[.]” Instead, Tom Stephens wrote in the EC newsletter, the environmental community had to insist on the “sustainable development of these communities, instead of the ‘jobs blackmail’ of industrial development at any price. (FGU, 31.1, pg. 4)”