Working with Labor: A Green-Blue Connection

The Ecology Center and the UAW

During the 20th century, the economy of southeast Michigan was synonymous with automotive manufacture. The “Big Three” of Ford, Chrysler, and General Motors captured national attention but hundreds of other businesses supplied parts and labor. It was in the vehicle sector where the Ecology Center found new alliances with organized labor focused on working conditions, transparency, and environmental impact. At first glance the UAW might seem like an unusual union for staff of an environmental organization to join (though the organization had provided seed funding for the first Earth Day in 1970), but in October 1990 Ecology Center employees became the first environmentalists to join UAW District 65. Cooperation between the labor (blue) and environmental (green) movements formed one of the “most significant positive development[s] within the environmental movement (ER, 22.10, pg. 2)” of the 1990s.

Labor organizing around issues of exposure to toxics, worker safety, and right to know contained a strong environmental orientation; it was these shared purposes that drove cooperation. In the 1990s, partnerships between the two movements included Right-to-Know campaigns organized with the UAW and firefighters, joint efforts advocating pesticide reform developed with the Farm Workers and Farm Labor Organizing Committee, and cooperation with the municipal employees’ union to promote recycling and progressive solid waste measures. For their part, environmental organizers identified the unsustainable use of human labor and non-human resources as part of a general attitude of short-term exploitation at the expense of long-term climatic health.

Though the UAW was also involved in evaluating industrial processes they saw a partnership with the Ecology Center as an opportunity to jointly interact with environmental organizations on efforts that protected worker health and environmental safety. On the question of auto pollution more generally, the UAW saw their goal as ensuring “the protection of auto workers and their jobs, to get firm commitments from the participants is toxic use reduction, not just pollution prevention, to expand the program continent wide if successful in the Great Lakes region. (Bentley, Ecology Center Records, Box 21, UAW Correspondence)”

Johnson Controls

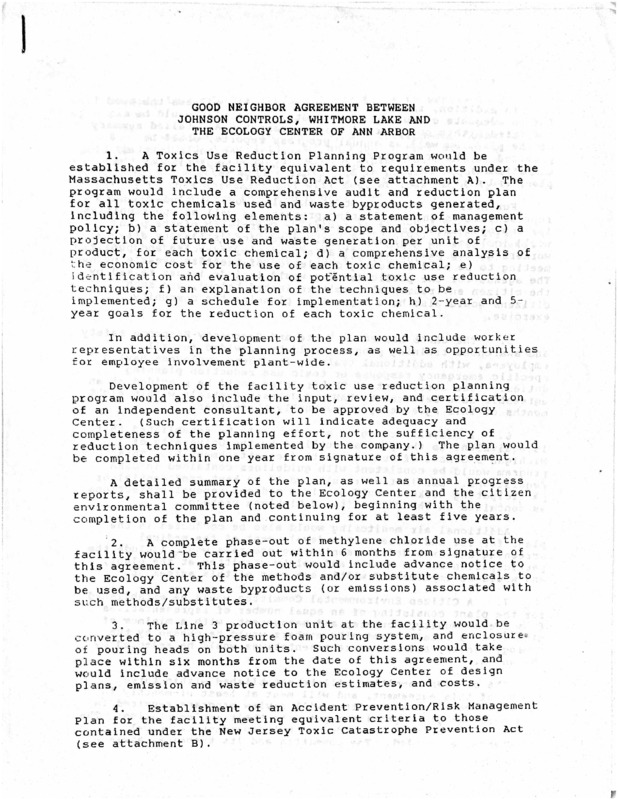

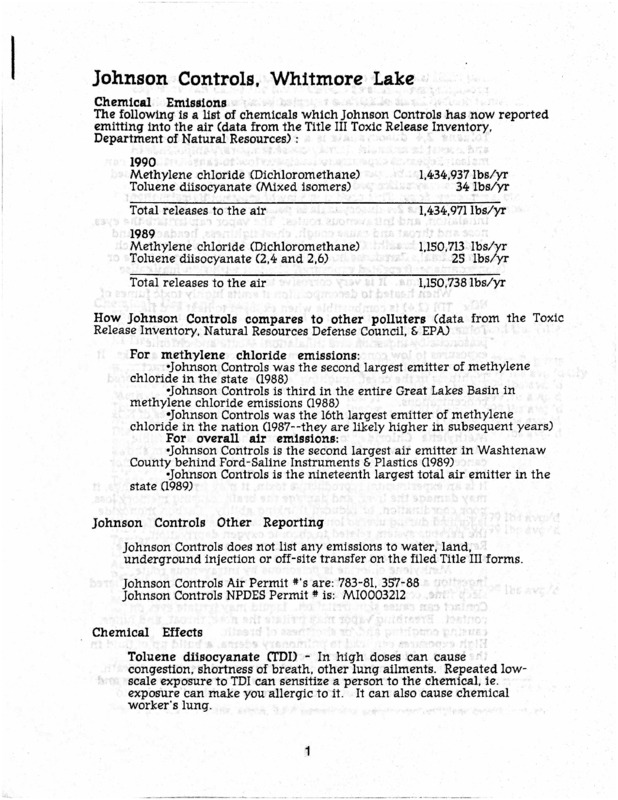

In September 1991, an Ecology Center lawsuit against Johnson Controls created an environmental and labor coalition around a local issue. The court action claimed the company’s plant in Whitmore Lake, ten miles north of Ann Arbor, operated in violation of federal community-right-to-know laws. Johnson Controls had failed to disclose annual emissions of over a million pounds of methylene chloride which made it the second-largest emitter of that chemical in the state. Alongside legal action, the Ecology Center began negotiations with the company to improve community safety, upgrade a production line which would reduce worker exposure to toxics, and commit to a toxics reduction plan.

By the year’s end, a federal judge allowed the Ecology Center’s suit to go forward while the EC worked out a settlement with Johnson Controls. The settlement focused on JCI making environmental improvements in lieu of significant monetary fines. In crafting the agreement, the EC worked closely with the UAW local leadership to develop the proposal company’s agreement to modernize production lines. Pitched as being good for both business and the environment a UAW press release about the lawsuit acknowledged that “environmentalists are beginning to recognize that the fight to reduce toxics must recognize the widespread contamination of workers[.] (Bentley, Ecology Center Records, Box 2-13, UAW Press Release)”

In May 1992, Johnson Controls indicated it would stop the release of methylene chloride at the Whitmore Lake facility. Finally, in December 1996 the EC reached a settlement with the facility (now owned by Woodbridge Corporation). In lieu of a fine the resolution included setting up a Washtenaw County hazardous materials team and contributing $6,000 toward Whitmore Lake organizations working on environmental issues and education (ER, 28.5, pg. 5). When considered alongside the modernized production lines the resolution of the lawsuit revealed the collaborative work of employees of JCI, members of UAW 157, and Whitmore Lake residents in developing demands made by the suit.

Charles Griffith interview, 13:59-20:24 - discusses Johnson Controls

Towards the Green Vehicle Challenge Campaign

As the decade drew to a close, the Ecology Center expanded its vision of how labor, the environment, and manufacturing were connected. The EC launched a Green Vehicle Challenge Campaign focused on addressing the impacts of production, questions of how to move forward with reducing the impact of production while pushing for higher efficiency vehicles, phasing out toxic materials, and changing both consumer and producer behaviors. With Michigan still number one state for automotive-related manufacturing jobs, the campaign emphasized the interdependence of economic and environmental elements.