See a related article from the Ecology Center's website, The Fight Against Developers to Stop Suburban Sprawl: Part 1

Anti-Sprawl I: Natural Features Ordinances

"What is at issue are the needless negative impacts that unwise development has and can have upon our sense of place, upon the quality of our lives, upon our economic and social well-being” - Christopher Graham, Ecology Report, vol. 26, no 4, Oct. 1994

In the late 1980s and 1990s, rapid population growth in Washtenaw county created new challenges for environmentalists in the region. On the one hand, more households generated solid waste management issues, as available landfill space in the county was shrinking rapidly. More serious and complex than landfill space, however, was urban sprawl. A Trend Future Report defined sprawl as “land development that lacks a functional relationship to land, is auto dependent, and that requires excessive road construction.” According to the Ecology Center’s Mike Garfield, in a July 22, 2019 interview, Michigan law allowed local units of government, like townships and cities, more control over development and land use than in most other states. The presence of many layers of authority and the absence of an overall regional plan contributed to growth that often transpired without reference to the big picture.

Like many environmental issues, urban sprawl was not a single-stakeholder issue. Rather, multiple groups were concerned about sprawl for different reasons. Washtenaw county residents worried about changes to their lifestyle if the region became suburbanized. Environmentalists feared the loss of natural resources and farmland. Social justice advocates worried about broader development patterns contributing to ongoing “white flight” from urban areas and drawing infrastructure away from cities with large populations of color.

The Ecology Center would fight on all of these fronts in their campaign against sprawl throughout the decade. In the first half of the 1990s, however, reforming natural features protections took center stage in Washtenaw County.

Context on Natural Features “Guidelines”

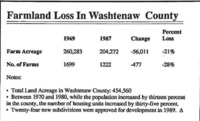

Non-agricultural development expanded as a corollary of the county's growing population. According to the August-September 1990 Ecology Report, the Washtenaw County saw a 21% loss of farmland between 1969 and 1987. The approval of 24 subdivisions in 1989, largely situated beyond existing urban boundaries, suggested that the loss of available farmland was not going to cease anytime soon.

Aware of these land use issues, Ann Arbor City Council attempted to take action in the late 1980s. A 1987 city planning inventory identified 31 “valuable sites” in Ann Arbor containing natural features that ought to be protected. The inventory also specified 57 wetlands and 28 woodlots within these sites. To protect these natural features, City Council drafted a series of guidelines in 1988-89 that would limit development and discourage environmentally harmful behaviors, like air pollution or waste dumping, near these sites.

The problem with these guidelines, however, was that they were just that - only guidelines - with little in the way of penalty or enforcement. The Ecology Center and other environmentalist organizations, like the local chapter of the Sierra Club, soon learned that the guidelines were being widely ignored. In 1991, going against guidelines, developers from the Guenther Building Company cleared 25 acres of trees, sold them to a logging corporation for profit, and consequently exposed a nearby stream to damage from erosion. Additionally, construction in the Newport Woods subdivision threatened a 150-year-old oak tree. With development in Washtenaw County showing no signs of slowing down, these guidelines would not suffice for long.

Reforming Natural Features Ordinances

The Ecology Center participated alongside a number of local environmental organizations to reform Washtenaw County’s land use guidelines and establish real protection for the county's natural features. One of these organizations was the Potawatomi Community Land Trust (PCLT), known today as the Legacy Land Conservancy. Incorporated in 1989, the PCLT aimed to protect farmland from pesticide contamination, soil degradation, and urban sprawl by holding land in trust and preserving it for the benefit of the community. The PCLT also aimed to make land more affordable for farmers by leasing land at low cost to farmers who used organic methods.

The Ecology Center became directly involved in land use issues by joining the county's Natural Features Ordinance Committee, which planned to reform the natural features guidelines to be both more streamlined and contain stricter regulations and enforcement provisions. Partnering with Kim Waldo of the Michigan chapter of the Sierra Club, the Ecology Center’s Mike Garfield issued new recommendations to the Natural Features Ordinance Committee. These included:

-

Require activity in and near wetlands, watercourses and woodlands take into account the quality of those natural features

-

Protect landmark trees of a minimum size

-

Require that protection measures be in place before site plans are approved

By the fall of 1992, several new regulations were put in place. Chapter 60, on wetlands and watercourses preservation, provided new standards for permits to build on wetlands and required permits to disturb, fill, or drain soils. In a similar vein, Chapter 63 issued protections for soil erosion and sedimentation, introducing significant new measures for preserving trees and woodlands.

The most contentious area of reform, however would be over anti-sprawl regulations themselves. While the preservation of natural features received general support, multiple stakeholders emerged in the fight for and against urban sprawl - with significant economic interests shaping their political positions and support or opposition to sprawl. The Ecology Center and other environmentalist organizations would encounter these opponents in full force by the decade’s end.