Anti-Sprawl II: PDR and Proposal 1

While natural features ordinances were the primary political tool to preserve open spaces in the early 1990s, environmentalists shifted their focus to try to prevent sprawl entirely in the decade’s later years. If action was not taken, Michigan was on pace to develop an additional 40% of its land in the next 20 years, creating new problems for both land conservation and pollution. The Ecology Center participated in a number of coalitions dedicated to preserving farmland and other open spaces from further development, including the Michigan Environmental Council Land Use Initiative, the Huron Land Use Alliance, and the Washtenaw County Agricultural Lands and Open Space Task Force. These groups conducted research on urban sprawl in Michigan and also spoke with local farmers to include their perspectives on land use issues. One common solution emerged from these coalitions efforts: purchase and development rights, or PDR. Upon receiving the Task Force’s recommendations to pursue PDR, the Washtenaw County Board of Commissioners approved a land preservation ballot proposal for the November 1998 ballot, known as Proposal 1. However, Proposal 1’s opponents were prepared to launch an aggressive counter-attack, raising the most money to oppose a local ballot campaign in county history.

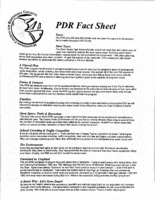

Understanding PDR

Purchase and development rights (PDR) emerged as the most comprehensive and actionable strategy for land use activists in the 1990s. As Mike Garfield explains in a July 22, 2019 interview, PDR allows for public or private entities to acquire land and keep it protected from development. Land that would otherwise be sold to developers and transformed into a subdivision can now remain untouched. Garfield notes that PDR promised a particularly useful strategy at the local level:

"We knew at that time, and this is the 1990s when there was a very conservative administration in Lansing that was not at all amenable to these sorts of policy measures, we figured we had to take action locally. When we looked at what was available to us, we realized that the most effective thing we could do at the local level would be to try to stop sprawl right at the source and block developments on farmland and areas that should be protected in rural areas.”

Importantly, a precedent for PDR existed in Michigan. In 1994, Traverse City Township passed an ordinance that would allow residents to obtain PDRs to preserve farmlands. This campaign was successful at the township level. The Ecology Center, alongside their collaborators, wanted to take the campaign first to the county level, and then to the state.

PDR also played a significant role in the Agricultural Lands and Open Space Task Force’s report to the Washtenaw County Board of Commissioners in 1997. Their report made seven key recommendations, noting that agriculture and open space lands had been adversely affected by development, and that legislation needed to be put in place to better regulate growth. They acknowledged that PDR was a significant strategy to help achieve these goals.

Proposal 1 Supporters: Save Our Land, Save Our Future

In response to the task force’s report, the county Board of Commissioners approved a ballot proposal, known as Proposal 1, that included several land preservation measures. The proposal suggested a 0.4 mill property tax increase--amounting to about $26 per household per year-- that would generate about $30 million over 10 years. Of the funds raised, 50 percent would be allocated for farmland preservation under PDR. The proposal also called for the outright purchase of open lands, and aimed to redirect growth in already populated areas where infrastructure was in place and could be maintained or upgraded rather than built from scratch.

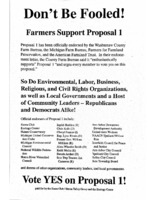

Proposal 1 quickly obtained widespread, bipartisan approval. Not only was the proposal backed by the county Board of Commissioners; it also received support from major public officials in Washtenaw County, endorsements from environmental organizations like the Sierra Club and National Wildlife Foundation, and approval from social justice and labor coalitions, including the UAW and NAACP. Importantly, local farm organizations also supported the proposal, and the Michigan Farm Bureau also endorsed it.

Throughout the summer of 1998, supporters for the proposal worked together under the campaign “Save Our Land, Save Our Future.” Lana Pollack and Keith Molin led the campaign and promoted educational efforts through canvassing, public debates, and publications in Ecology Report. The campaign prided itself on its bipartisanship as well as its widespread representation from the business, political, activist, and agricultural sectors.

Proposal 1 Opposition: Washtenaw Citizens for Responsible Growth

Despite widespread bipartisan support for Proposal 1, the proposal’s opponents waged a comprehensive counter-campaign. The primary opponent was the Washtenaw County Homebuilders’ Association, along with the Realtors’ Association. According to Garfield, these groups feared that the county-level Proposal 1 would soon lead to state-wide efforts to control sprawl. They saw the proposal as a definitive test case, and raised upwards of $250,000 to oppose it.

The opponents branded themselves as “Washtenaw Citizens for Responsible Growth” and criticized Proposal 1 as being “anti-growth,” as opposed to “anti-sprawl.” The opposition based their campaign primarily on misinformation, arguing that the proposal would actually be harmful to farmers and that higher taxes would make housing unaffordable. As one fact sheet phrased it, “Farmlands are already developed: they have no biodiversity, they have pesticides dumped on them, and they have heavy equipment rolling over them. Clearly, the PDR tax will NOT benefit the environment.”

Washtenaw Citizens for Responsible Growth coordinated their campaign primarily through television ads, which was a first for local political campaigns in the county. They also publicly debated supporters of Proposal 1 and relentlessly criticized the tax hikes. Although the Ecology Center helped coordinate one of the largest grassroots campaigns in county history, they could not compete with the opposition’s ads. On November 3, 1998, Proposal 1 was defeated, receiving only 42 percent of the vote.

Regrouping after Proposal 1 Fails to Pass

The Proposal 1 defeat was difficult for Save Our Land, Save Our Future and the Ecology Center, especially when it was revealed that 98 percent of Washtenaw Citizens for Responsible Growth’s donations came from the homebuilding industry. To regroup, the Ecology Center continued to partner with local organizations, including the Sierra Club and the Washtenaw County Farm Bureau to pass smaller portions of Proposal 1 in stages. These measures included new natural features ordinances in 1999 and 2000. Despite the loss in a five-year effort to improve land protections, the Ecology Center and its collaborators would bide their time and seek comprehensive land reform once more during the Greenbelt Campaign in 2003.

Article written by Katherine Hummel, member of the Spring/Summer 2019 Research team.