The Origins of Health Care without Harm in Southeast Michigan

As the Ecology Center turned its attention towards environmental health initiatives and ending incineration, they could draw from a growing body of scientific evidence. Throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, the Environmental Protection Agency released several rounds of new information regarding the role of incinerator emissions in producing dioxin and mercury, two substances that posed grave consequences for human health. Dioxin resulted from burning chlorinated substances, including many PVC plastics, and mercury entered the waste stream in materials like batteries. Both dioxin and mercury are also bioaccumulative, meaning they build up over time in plants and animals and reach humans through the food chain.

As an alternative to landfilling, commercial incinerators were active throughout Michigan. While large-scale incinerators introduced mercury into the environment, the EPA's findings identified a new incineration source: medical waste incinerators affiliated with health care systems. With no state-level regulations issued by the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality, medical waste incinerators were free to operate without fear of legal consequence. Ironically, the industry that pledged the Hippocratic Oath to “do no harm” to its patients was the leading source of dioxin- and mercury-related incineration emissions.

Health Care without Harm

1996 would prove to be a watershed year for building bridges between environmental and human health. Just three years after the EPA’s latest round of guidelines placed a moratorium on incineration, a team of environmental scientists and journalists published Our Stolen Future, a nonfiction book that explored the theory of environmental endocrine disruptors. Researched by Dr. Theo Colborn, "the Rachel Carson of the 1990s," endocrine disruptor theory argues that environmental toxins can produce adverse health effects in humans, and that these effects can be transferred across generations. A significant portion of Colborn’s research focused on case studies from the Great Lakes, a focus that motivated Tracey Easthope and the Ecology Center to form the Michigan Environmental Health Coalition. However, on a national scale, the dual factors of the EPA’s guidelines and Colborn’s research also spurred other groups to increase their focus on the health care sector's environmental impact.

One of these groups was Health Care without Harm (HCWH), a coalition of health care associations, environmental activists, and community organizers committed to improving the health care industry’s environmental footprint. In an August 6, 2019 interview, founder Gary Cohen explained how the coalition was born through a series of gatherings held throughout 1996 in California and Louisiana. As the organization grew to confront multiple health-care systems nationwide, Cohen repeatedly returned to the principle of “do no harm” as a reason for hospitals to improve their environmental impacts:

"How do you poison your neighbors in the service of healing them? How can you get away with that? How can you dump waste into incinerators and into people’s air and ultimately into their food as part of your healing mission?...We kept holding up the Hippocratic Oath as something they abide by that they needed to address from the point of view of their emissions, their supply chain, the energy they use, the food they bought, the chemicals they used and exposed patients and employees to.”

Easthope attended several of these meetings and brought Detroit's concerns about medical waste incineration to Cohen’s attention. HCWH had found its first regional partner in the Ecology Center.

Local Campaigns against Medical Waste Incinerators

Between 1980 and 2001, Henry Ford Health Systems operated a large medical waste incinerator (MWI) at its flagship hospital in Detroit. A patient with a south facing view would have likely seen the smoke. In fact, as one story goes, a patient from her hospital bed called the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) to complain about it. But few took as much notice of the incinerator as the residents of the Virginia Park neighborhood. Charles Greiss, a 71 year old retired truck driver, made his concern known to the Detroit News in 1999, wondering aloud to the reporter, "What's in that smoke? What's it going to do to my babies?"

Greiss had a reason to be concerned. In the smoke were the noxious vestiges of burnt medical equipment: IV bags, food trays, broken thermometers. While incineration of any kind poses a threat to health and the environment, medical waste can be especially pernicious. Hospitals use a tremendous amount of chlorinated plastics which, when burned, can release dioxin, a harmful carcinogen. Mercury, a powerful neurotoxin, was also abundant in hospital waste in the 1980s and 1990s. Both mercury and dioxin can quickly accumulate in the food chain and body, making them harmful at relatively small levels.

Despite their mandate to “do no harm”, over 150 hospitals in Michigan opted to burn rather than treat their solid waste in the early and mid 1990s. The reasons for these decisions were varied and complex. For one, the federal and state regulations around MWIs were relatively weak or not existent. Taking advantage of the lax regulations, incinerator, plastics, and medical supply companies went to great lengths to assure hospital officials that medical waste could be burned in compliance with the law. As hospitals burned more disposable items, the market for and availability of reusable medical equipment shrank, leading to greater waste streams. In the late 1990s, advocates finally got federal regulators to put emission limits on medical waste incinerators. This forced smaller hospitals with onsite incinerators to transition to alternative waste management processes. Many large hospitals, however, doubled down on incineration, investing in multi-million dollar pollution abatement technology. Once the money was spent, these hospitals became even more reluctant to transition away from incineration, even when abatement failed to reduce emissions to safe levels.

Poorer communities and communities of color in Michigan bore the worst effects of MWIs. Henry Ford Health Systems is perhaps the starkest example. While it’s main hospital burned its waste in the majority-Black Virginia Park neighborhood, its suburban branches in wealthier and whiter areas shipped their waste elsewhere. Three miles northeast of Henry Ford was the large commercial incinerator in Hamtramck, a majority immigrant enclave engulfed by Detroit. Residents near both incinerators experienced some of the highest rates of asthma in the state, which made them especially vulnerable to airborne toxics (which may have also been the cause of their asthma). Although Ann Arbor was and is wealthier and whiter than Hamtramck or Detroit, the U-M hospital’s incinerator was located in the poorest census tracts of the city, where median income was just under $11,000 in 1990. Together these three incinerators caused untold damage to Southeast Michigan. For instance, The National Wildlife Federation (NWF) released a report in 1999 that found that areas in and around Detroit were experiencing mercury contamination at 65 times the EPA standards.

The Ecology Center’s various roles in these efforts serve as an important case study in how an organization can leverage the expertise of community members, scientists, and medical professionals in pushing for both regional and national changes to healthcare. This history also highlights how the strategies of public pressure and friendly cooperation can be used together to transform industries who are either unaware of their environmental footprint or are simply stuck in the old way of doing things.

The Ecology Center Wades Into the Centuries Old Problem of Medical Waste

Prior to the 19th Century, hospitals were often vectors of disease and illness as much as they were places of healing. Thanks to the work of public health scholars, like Florence Nightingale, sanitizing equipment and disposing of infectious waste came to be seen as critical to hospital operations. Sterilization and proper waste management, however, is tedious and prone to error. Starting in the mid 20th century, vinyl and medical supply companies promoted disposable plastics as a cheaper and safer alternative for much of the hospital supply chain. By the 1980s, plastic made up about 30 percent of the medical waste stream (Thorton et al). Around the same time, many hospitals turned to incineration as a sterile and scalable way to deal with all this disposable waste. The appeal of both disposables and incineration increased as a result of the HIV-AIDS epidemic in the 1980s.

It wasn’t long until scientists and environmental advocates became concerned about what hospitals were burning. Their studies reported on the dangerous potentials of burning items that contained lead, mercury, cadmium or harmful chemicals associated with treatments like chemotherapy. In 1990, Congress took a first step by amending the Clean Air Act to account for medical waste. The legislation, however, failed to yield EPA regulations that would hold hospitals to account. In 1997, Earthjustice, with the Ecology Center as a signatory, successfully sued the EPA to bolster its regulation of MWIs. Under pressure by environmental activists, the American Hospital Association (AHA) also entered into a voluntary agreement with the EPA to cut hospital waste in half by 2010 (they would renege on that agreement just three years later).

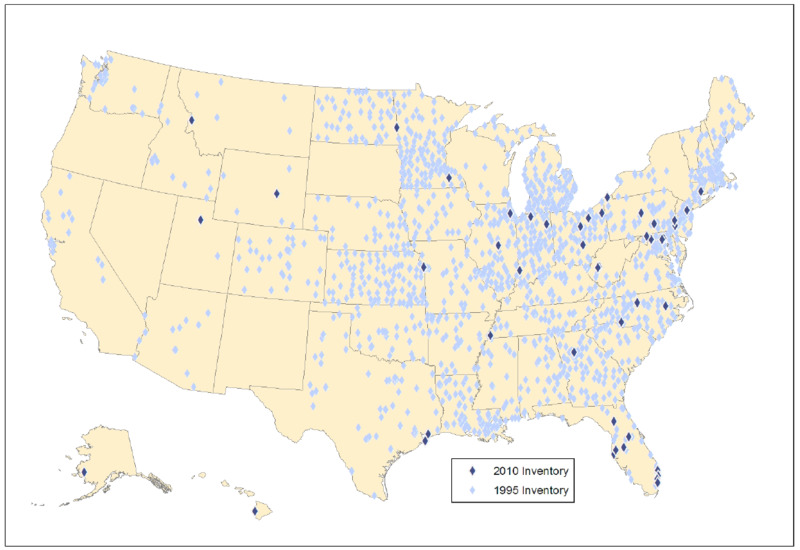

The new EPA regulations of 1997 effectively forced smaller and medium sized incinerators to shut down, reducing the number of MWIs in the US from 4,500 in 1995 to just 57 in 2010.

In Michigan, the number of incinerators decreased from 157 to 50 in just three years. Many of these hospitals shifted to a waste treatment process known as autoclaving. In autoclaving, infectious waste is heat sterilized in large cement-truck-like cylinders so that it can be safely buried in a landfill. Among the early leaders in Southeast Michigan to adopt autoclaving was St. Joseph Mercy Hospital in Ypsilanti, which closed it’s incinerator in 1996.

Unlike smaller hospitals, large hospitals and waste companies could afford to purchase expensive pollution abatement technologies to reach the EPA’s modest standards, and several of them did. This proved to be a major concern for Easthope at the Ecology Center, who argued that neither EPA standards nor existing abatement technology were adequate to protect the safety of the environment and communities surrounding the incinerators. Additionally, burning waste stood as an impediment to reusing and recovering materials. As a result, the Ecology Center turned a great deal of its attention in the 1990s to shutting down three of the largest remaining incinerators in Michigan, those located at: U-M, Henry Ford Hospital, and Hamtramck.

The Coalition to Shut Down the Henry Ford Incinerator

The Ecology Center and a coalition of community and national activists had been involved in a fight to shut down Henry Ford’s MWI since the mid 1990s. The residents of Virginia Park played a major role in this effort. Located on the north side of the New Center area in Detroit, Virginia Park has had a long history of responding to racial injustices. One of the major channels for residents’ activism was the Virginia Park Citizens District Council (VPCDC), a neighborhood organization headed at the time by James Williams who was instrumental in raising awareness about Henry Ford’s WMI.

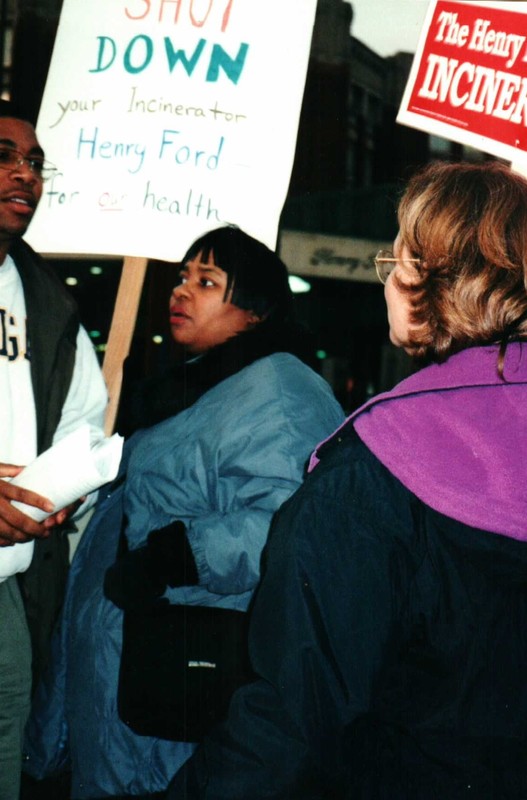

In 1998, VPCDC joined forces with the Ecology Center and several other local and national organizations in what would become The Coalition to Shut Down Henry Ford Incinerator. The coalition also included the National Wildlife Federation, Detroiters Working For Environmental Justice (DWEJ), the Southeast Michigan Group of the Sierra Club, the Sugar Law Center for Economic and Social Justice, the Arab Community Center for Economic and Social Services (ACCESS), and the Michigan Chapter of the American Lung Association. DWEJ in particular played a critical role in organizing the Virginia Park residents in campaigning against Henry Ford’s Medical Waste incinerator. DWEJ’s Executive Director at the time, Donele Wilkins, led much of this work.

Coalition partner, Guy O. Williams, then a National Wildlife Federation employee and EC Board Member, explained that the coalition had an inside and outside front. The “inside” front brought EC scientists to the table with Henry Ford staff to explain the science behind alternatives to medical waste incineration. At the same time, the “outside” front elevated community voices through demonstrations and pickets outside the hospital, using the Sweet Home Baptist Church across the street as a frequent meeting place.

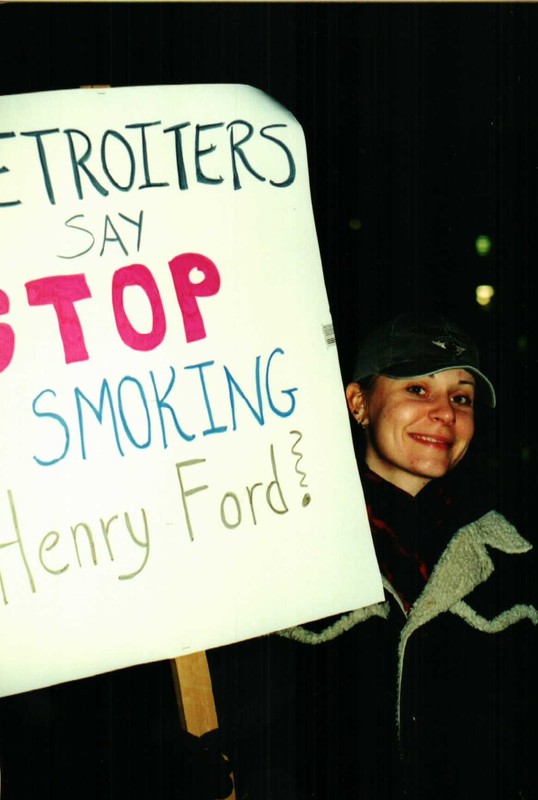

With its coalition partners, the Ecology Center worked to educate hospital administrators and apply outside pressure on the hospital to make changes. Coalition members furnished yard signs that read “"Shut It Down, Henry Ford", sent hundreds of letters to Senior Vice President of Henry Ford Nancy Schlichting, testified at public hearings, and organized several protests at Henry Ford. Shortly after the coalition formed, Henry Ford uninstalled a $2.1 million pollution control system at its MWI. With the hospital signaling its continued commitment to incineration, the coalition countered by increasing its public pressure campaign.

With yard signs and occasional protests visible to patients and staff entering the building, the incinerator quickly became a public relations nightmare for administrators at Henry Ford. With the public pressure campaign heating up from the outside, the Ecology Center and other coalition members continued to meet with hospital leaders to promote safer alternatives to incineration. The efforts received an added boost when Schlichting, a more empathetic ear to the campaign, became CEO of Henry Ford in 2000. Shortly after she took the position, Schlichting announced that Henry Ford would switch from incineration to autoclaving.

Henry Ford officially closed the MWI on June 15th 2001, but refused to acknowledge any wrongdoing. In a statement to the Detroit Free Press, a Henry Ford spokesperson said, "We decided as an organization to be responsible and sensitive neighbors and shut it down, even though we know it operates within all the requirements and is safe.”

Pulling the Plug on Incineration at U-M and Hamtramck

The Ecology Center, HCWH, and other coalition partners also worked to shut down the incinerators at U-M and Hamtramck. From 1994 to 1999, the Ecology Center increased its pressure on Gil Omenn, president of the U-M Health System, to switch to a safer disposal method for its 3,000 tons of annual waste. In this effort, Easthope made the case for closure in the Ann Arbor News and Michigan Daily, arguing that the incinerator was neither cost effective nor safe for the university. The Ecology Center also helped to organize a U-M student chapter of HCWH (“Students for a Healthy Hospital”), attended multiple meetings with U-M hospital administrators, and had brought together a coalition of local and national activist groups, including NWF, the Sierra Club, the Huron River Watershed Council, and the Public Interest Research Group in Michigan. Faced with growing public pressure, Gil Omenn, then CEO of the university health system, approved a task force to investigate alternatives. Later that year, U-M announced it would close down its MWI, the third largest in the state at the time.

The same year that the Ecology Center began it’s campaign at U-M, Rob Cedar, a Hamtramck resident, organized the Hamtramck Environmental Action Team (HEAT) to coordinate a campaign against his city’s incinerator. Cedar eventually won a seat on the Hamtramck City Council and worked with the Ecology Center and HCWH to bring pressure on the facility to shut down. A few years later, ACCESS joined the coalition helping to represent the voices of Hamtramck’s large Arab and Middle Eastern community.

In early 2005, after a prolonged campaign waged by Hamtramck citizens and coalition members, MDEQ finally announced that it would revoke the permit for incineration at the plant. With the closure of the Hamtramck MWI, medical waste incineration became a relic of Michigan’s past.

The Legacy of the Medical Waste Fights

The Ecology Center and its coalition partners’ decade-long campaign to close MWIs in Michigan was an unequivocal success. The problem of waste, however, remained. Autoclaving had proven a cheaper and cleaner alternative to MWI, but much of the waste still ended up in landfills. As a result, the Ecology Center continued to work with hospitals to help them reduce the toxicity of the products they use, and the volume of their waste streams by switching to more reusable equipment. This effort also took the convincing of major medical parts suppliers to produce more reusable products.

The Ecology Center helped lead the Safer Materials workgroup of HCWH, for which it was a founding member for more than 20 years The Ecology Center continues its association with HCWH today, now with a global portfolio of issues ranging from toxics to climate change.

In this campaign, the Ecology Center learned the importance of developing strong partnerships with healthcare leaders. In 2014, it launched its Health Leaders Fellowship initiative, aimed at training doctors, nurses, and administrators to be environmental and public health advocates. The Ecology Center has gotten involved in other healthcare sector projects, such as initiatives to connect hospitals with healthy, sustainable food sources (Healthy Food in Healthcare , Cultivate Michigan and MFIN AND, Fresh prescription).

The campaign to shut down the incinerators also helped to manifest one of its major operating strategies: forming powerful coalitions and helping to empower local communities. As Easthope said in a 2019 interview, "When we enter a community, we do not want to take over that fight. We don’t want to be the most prominent people in that fight. We want to elevate the community because that’s where they live, that’s where they’re from. We want to actually elevate and build capacity in the community to continue whatever work to improve the environment that needs to continue."