Expanding Grassroots Toxics Organizing

Since its founding, the Ecology Center had made local toxics organizing a priority, from running household toxics collection days to developing a toxics curriculum for Ann Arbor public schools. During the 1990s, the EC’s advocacy surrounding toxics expanded to reach regional, national, and even international levels. The Toxics Reduction Project, initially run by staff members Charles Griffith and Tracey Easthope, grew into two major sectors: "green-blue" organizing largely in conjunction with the auto industry and environmental health advocacy. Both initiatives focused on the relationship between environmental health and human health. The intersection of these two issues grew into a key focus area for the Ecology Center.

Toxics Reduction Project

The Toxics Reduction Project was directly related to the Ecology Center’s advocacy in passing both local and state-level right-to-know legislation during the 1980s. Although these laws required that businesses and manufacturers reveal potentially hazardous contents in their products, much work still remained to educate consumers about what, exactly, was harmful.

Charles Griffith, one of the lead organizers of the campaign for a local right-to-know ordinance, directed the Toxics Reduction Project. He welcomed a new staff member, Tracey Easthope, to the team in 1990. Supported by a grant from the C.S. Mott Foundation the EC began developing community outreach programs that aimed to inform citizens about potentially harmful elements present within their environment.

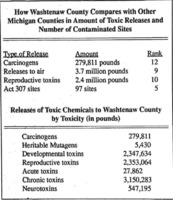

The Toxics Reduction Project also undertook research to better understand the extent of hazardous waste in Michigan. Drawing on data from the Toxics Release Inventory (TRI), Griffith and Easthope realized that Washtenaw County had the dubious honor of ranking twelfth in the level of carcinogens, tenth in developmental toxins, and fifth in hazardous waste sites among the state's 83 counties. Having this state-wide data at their disposal made the elevated presence of toxics visible to a wider population and provided a basis for the EC adopting an aggressive agenda against hazardous waste, and specifically against sources like landfilling, incineration, and cement kilns.

As part of their agenda, the Toxics Reduction Project started their own newsletter to communicate toxics-related information to the public. Michigan Toxics Watch was published from 1990-1995 as a supplement to the EC's regular newsletter, Ecology Report, by drawing readers’ attention to toxics issues in southeast Michigan. Each issue featured a local grassroots activist and profiled their cause for the wider Toxics Watch readership. Activists included Linda Caswell, who campaigned against paper companies dumping waste into the Au Sable and Manistee Rivers, and John Nasarzewski, who spearheaded the Monguagon Creek cleanup in Wayne county. The newsletter became a platform for raising the profile of both the Ecology Center and anti-toxics advocates in the region.

This regional partnership was put on full display when the Toxics Reduction Project helped to organize a demonstration of the Great Lakes Health Banner (GLHB) project in Lansing on October 13, 1993. Founded by Maryann Stroup, whose infant daughter died from a rare form of leukemia, the GLHB gathered 90 grassroots organizations and activists who wanted the state of Michigan to develop a stronger stance on environmental issues. Each organization made their own cloth banner and decorated it with slogans and symbols representing their cause. The organizers demanded that Governor Engler and the state Department of Public Health endorse the International Joint Commission’s report on toxins in the Great Lakes, take action against the Alpena Lafarge cement kiln, and test schools for electromagnetic radiation.

New Science, New Collaborations: The Michigan Environmental Health Coalition

The GLHB campaign marked a turning point both in the future of the Toxics Reduction Project and in the way that the EC conceptualized environmental health. Not long after the Lansing demonstration, the Toxics Reduction Project began to expand along two parallel but distinct avenues. Charles Griffith began building new partnerships with labor organizations through the Auto Project and Tracey Easthope explored collaborations between environmental and health care groups.

As Easthope recalls in a July 19, 2019 interview, environmental science began to change after Dr. Theo Colburn - who became known as the Rachel Carson of the 1990s - published new research on endocrine disruptors in 1995 and 1996. Easthope explains the innovation of endocrine disruptive science:

"There’s this idea that your body’s message system, which is the endocrine system, that that can be disrupted. And if your message system is disrupted, all kinds of things could go wrong in the body. It was actually a new idea about how chemicals [work]...this idea that there could be lots of chemicals in the environment that we were exposed to, that were endocrine disruptors, was really a new idea.”

Because a significant portion of Colborn’s research was focused on the Great Lakes, environmental organizations, including the Ecology Center, used this information as an opportunity for renewed action. On December 2, 1995, the Ecology Center hosted a conference on endocrine disruption at Washtenaw County Community College. Titled “The Environmental Connection: Rising Rates of Breast Cancer, Reproductive Disorders, and Children’s Disease,” the conference brought together researchers, organizers, and activists who wanted to better understand the dangers of environmental endocrine disruptors. Keynote speakers included Dr. Devra Lee Davis of the World Resources Institute, Bella Abzug of the Women’s Environment and Development Organization, and Lois Gibbs, a key activist in the 1978 Love Canal disaster and the “grandmother” of the modern grassroots toxics movement.

The conference proved to be a success, so much so that the Ecology Center decided to take advantage of the momentum the event had generated about toxics. In 1996, Easthope and Mary Beth Doyle co-founded the Michigan Environmental Health Coalition. The MEHC included 36 organizations ranging from the Michigan Environmental Council to the League of Women Voters to Blossom Home Preschool. According to a membership handout, the Coalition’s mission was threefold: “To serve as a clearinghouse on environmental health issues; To advocate for prevention of pollution to protect human health; and to support grassroots struggles for healthy and safe communities.” The member organizations worked together on speaking tours, developing educational materials and environmental policy, and working to prevent endocrine disruptive diseases, such as breast cancer.

The Coalition produced several partnerships and launched campaigns that were active well into the 2000s. One of its first collaborations was with the newly formed organization Health Care without Harm (HCWH). Working to reduce the environmental footprint of the health care industry, HCWH introduced a “Healthy Hospital Campaign” to move hospitals away from toxic medical waste incineration.

The Coalition also began to investigate the use of toxins in everyday products like tin can linings and children’s toys. Some of these toxins, like Bisphenol A, were endocrine disruptors, but as the Coalition investigated further, they soon discovered that phthalates, a substance added to plastics to increase their flexibility and durability, were commonly used in vinyl children’s toys. These chemicals could leach into children’s mouths when the toys were chewed. The Coalition launched a strong campaign against “toxic toys,” including outreach with local schoolchildren. By 1999, KMart, Meijer, and Toys R Us all agreed to remove vinyl toys from their shelves. The ability of regional partnerships to raise awareness about environmental health hazards would prove useful as the Ecology Center expanded its product testing and advocacy with children’s health in the 2000s.