Toronto Trash and Return to Sender

At the beginning of the 1990s, Ann Arbor was all too familiar with strict environmental standards for new landfills required by the Michigan Department of Natural Resources. Few residents, then, might have guessed that at the end of the decade southeast Michigan would be selected as an ideal dumping ground for international trash. Despite the DNR’s requirements, once regulations were met it was surprisingly easy -and cheap - to dispose of waste in landfills throughout the state.

During the administration of Governor John Engler (1991-2003), Michigan's Department of Environmental Quality - a new unit created in 1995 to manage environmental regulation and permitting - allowed the opening more landfills than were necessary throughout the state of Michigan. As a result, the “tipping fees,” or waste disposal charges, at Michigan landfills were between 25% and 75% lower than other regional landfills, including those in Ontario, Canada.

In February 1997, the city of Toronto struck a deal with Browning-Ferris Industries to dispose of the entirety of the city's waste in BFI’s Arbor Hills landfills for a five-year period beginning in 1998. By the late 1990s, fifteen percent of material sent to Michigan landfills was already being imported. The Toronto deal promised to add an additional fifteen percent - estimated at 500,000 tons of garbage per year - to Michigan's garbage importation, all of which would be concentrated in Wayne County.

Legal Roadblocks

In 1997, not long after the BFI deal was announced, the Ecology Center took a leading role in campaigning against the decision to import waste. A new coalition, the Network of Waste Activists Stopping Trash Exports, or NO-WASTE, first attempted to pursue legal action to prevent international trash imports to Michigan. The group supported Senate Bill 4, which would have applied for authorization from the U.S. Congress to close Michigan’s borders to international waste. The key argument of the bill asserted that Michigan should be allowed to deny waste imported from states or provinces which had less restrictive disposal laws - for example, laws that allowed the mixing of hazardous materials, like batteries, with regular solid waste - than Michigan did. The legal argument was a difficult one and required Congressional approval to not put Michigan in violation of the Constitution’s provisions about interstate commerce.

Although legal action on the federal level seemed like the best solution, NO-WASTE was also aware that state-level legislation had allowed the Toronto-BFI deal to occur in the first place. In 1995, against the recommendation of county planners, the DNR approved an expansion of City Management’s Carleton Farms Landfill, located in Sumpter Township on the western border of Wayne county. The DNR approval of the measure set a precedent for state administrators to overrule county planners about landfills. The passage of House Bill 4037 in early 1997 eliminated the state’s oversight of county solid waste plans and the authority of counties to manage solid waste flow in local facilities. Instead of negotiating with county officials, landfill owners could now undertake private agreements between with individual townships or cities - exactly like the one between BFI and the city of Toronto. The bill had bipartisan support, and was sponsored by James Middaugh, a state representative who received campaign donations from waste industry PACs. With the state legislature and the broader Engler administration less-than-enthusiastic about landfill restrictions, NO-WASTE turned to other mobilization methods.

Return to Sender Trash Bash Tour

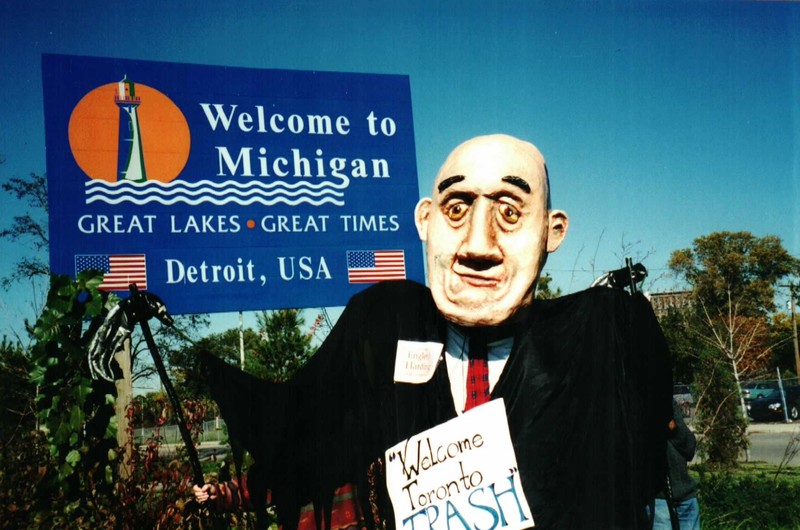

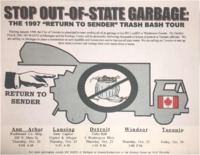

With the clock ticking until the first delivery of Toronto trash in January, 1998, NO-WASTE needed to develop a new strategy. In October, 1997, the “Return to Sender Trash Bash Tour” was born. Throughout the summer, Ecology Center activists helped organize a massive letter-writing campaign to Mel Lastman, the leading mayoral candidate in Toronto, pleading with him to cancel the deal with BFI. Letter-writers emphasized that trash imports would discourage Michigan citizens from recycling because of the perceived excess capacity to take waste from other cities. Additionally, the act of transporting garbage from Toronto to Michigan would use excessive amounts of fossil fuels. Initially these letters were going to be delivered to Toronto in a garbage bin, but as the campaign grew, NO-WASTE collected enough letters to fill an entire recycling truck.

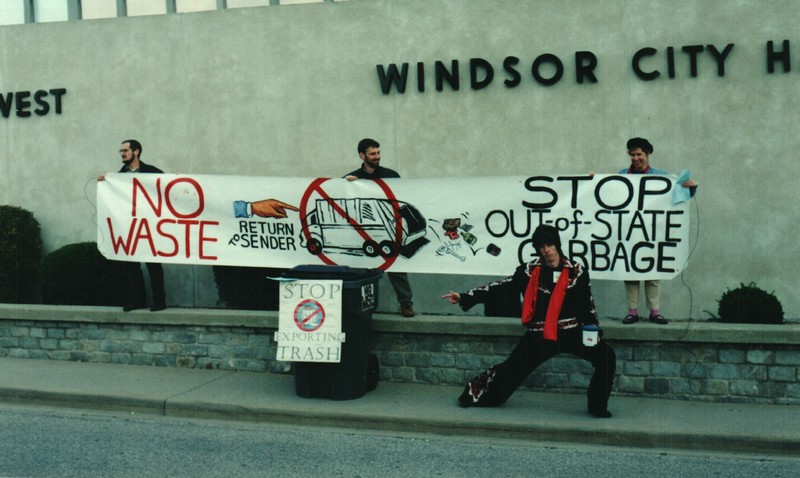

The “Return to Sender” campaign also took their inspiration from the Elvis Pressley song quite literally. Rather than drive straight to Toronto, the recycling truck became a tour bus. On October 23 and 24, the Return to Sender tour drove from Ann Arbor to Lansing, downtown Detroit, Windsor, Ontario, and then on to Toronto. At each stop, an Elvis impersonator emerged, singing a custom version of “Return to Sender” that made NO-WASTE’s message clear:

"Return to Sender / That address unknown / Don’t want your trash here / So keep it home!”

You can listen to the full song and view the full lyrics at left.

The Return to Sender Trash Bash tour understandably attracted a lot of attention, especially across the border in Windsor. While "Elvis" performed Return to Sender, NO-WASTE activists spoke with the media, reminding them that trash imports from Toronto would need to pass through Windsor enroute to Michigan. This would lead to traffic, as well as noise and air pollution. In Toronto, the truck pulled up directly to Mel Lastman’s campaign headquarters. Although he did not greet the group, NO-WASTE delivered the letters, as well as five bags of actual garbage. Jeff Surfus, NO-WASTE’s president, explained the bags were “a symbolic gesture of our appreciation for the forthcoming ‘gifts’ we are to receive from Toronto.”

Despite the attention and success of the first Return to Sender tour, the campaign continued over the next several years. In July, 1999, NO-WASTE encouraged a massive phone call campaign to the mayor’s office to end the trash imports. In May, 2000, the Ecology Center delivered testimony before the City of Toronto Works Committee to discuss alternative solid waste disposal options in Toronto.

Article written by Katherine Hummel, member of the Spring/Summer 2019 Research team.