Reforming Public Transportation

Following the birth of the modern environmental movement in 1970, environmental activists proclaimed that the time had come to end Americans’ dependence on the automobile. Decades of auto-centered urban planning had created a sprawling highway system that connected cities whose streets were overwhelmed with traffic, resulting in unsafe levels of pollution. In February 1972, the national lobbying organization Environmental Action explained in its newsletter how the construction of freeways and suburbs fed a “cycle of decay” that victimized the most vulnerable inner-city residents.

“Developers lure urbanites to suburbia with the promise of green surroundings and easy access to downtown jobs. Roads are built to provide the access. The combination of more freeways, more traffic and increased urban congestion and pollution draw more of the affluent to the suburbs — sometimes taking their corporations with them. The poor, unable to flee the city because of discrimination or because they cannot afford it, inherit the inner city.”

To make city life more liveable, environmentalists advocated a new approach to urban planning that de-centered the automobile. They encouraged cities to promote transportation alternatives like mass transit, bicycle use, and carpooling but had to compromise with skeptical politicians and corporate interests that were satisfied by the status quo. In Washington D.C., Environmental Action and its allies tracked auto-makers’ compliance with the Clean Air Act’s air quality standards and freed funding for mass transit by “busting” the Highway Trust Fund. In City Halls across the nation, local environmental organizations lobbied for more incremental changes to bus routes and city planning policies. In the 1970s, the staff of the Ecology Center offered their expertise and a new vision for transportation in and around Ann Arbor.

In August 1970, the Ecology Center called on the city of Ann Arbor to promote transportation policies that were environmentally sustainable and socially conscious. In particular, the Center requested that the Ann Arbor Transportation Authority (AATA), chartered in 1969, provide people throughout the Ann Arbor region with “inexpensive, rapid, convenient transport” that would reduce automobile dependency and pollution. Rapid population growth had overburdened the road system, while local public transit options were underfunded and inaccessible to many residents. Automobile-based planning discriminated against groups that lacked private transportation options, especially the elderly, the disabled, and lower-income families.

In its newsletter, the Ecology Center proclaimed that unless the city made environmental principles central to urban planning, the future of transportation in Ann Arbor would be grim:

“A continuation of the present alternative to private automobiles (which means virtually no alternative at all) will lead to increasing traffic jams, increasing air and noise pollution, escalating parking costs, and continuing numbers of parking structures and pedestrial horrors such as Huron Street. There will be more concrete, less foliage, faster and wider roads, and absolutely no space for human beings.”

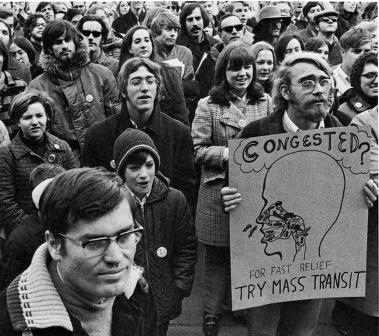

In the early 1970s, under pressure from environmentalists and the new left-wing Human Rights Party, the city briefly considered transforming transportation in Ann Arbor in a radical way. In October 1971, Mayor Robert Harris told the Michigan Daily that City Council was studying a proposal to block cars from traveling on several main streets to create pedestrian malls connected by shuttle buses. This vision of a pedestrian-oriented downtown centered around human activity faced powerful opposition. Several miles south of downtown Ann Arbor, Briarwood Mall was under construction, with free and plentiful parking. Downtown business-owners were filled with anxiety, certain that when Briarwood opened it would capture the crowds that once filled Main Street. This fear, combined with pressure from environmental organizations and neighborhood associations, gave the city a mandate to redesign transportation to revitalize downtown Ann Arbor and bring the crowds back.

Bringing more people downtown without cars faced many obstacles, including the underfunded city bus system which did not serve all sections of Ann Arbor equally. In September 1971, in a partnership with the Ford Motor Company and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the city of Ann Arbor established a door-to-door transportation service called Dial-A-Ride to supplement the city bus network. Through the service, people living in 2,100 households in southwest Ann Arbor could place a call and a ten-passenger minibus would arrive to carry them to the downtown business district. Dial-A-Ride was the second service of its kind in the United States and the first in Michigan. Despite this innovation, many commuters and other people living in outlying communities such as Ypsilanti did not yet have access to the public transportation system.

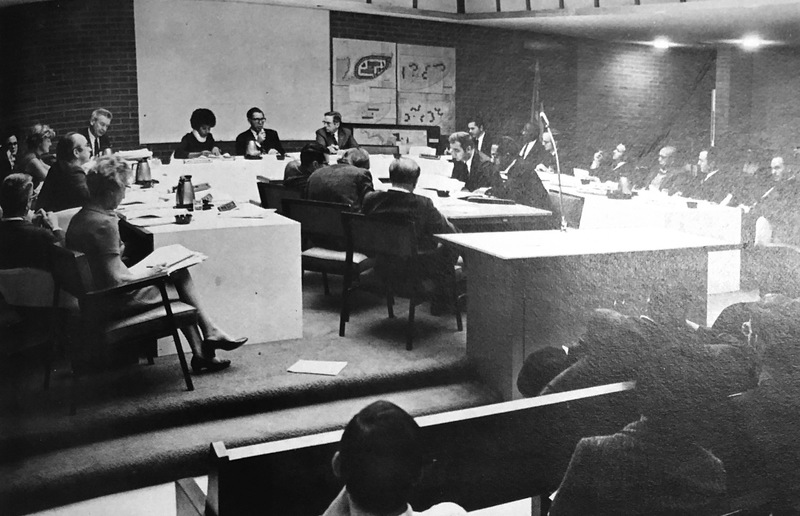

The environmentalists and their allies supported two transportation millages on the April 1973 ballot, a package which the Ecology Center called “the single most important environmental issue facing Ann Arbor in 1973.” A vote for Proposal A was a vote for Teltran, the AATA’s plan to expand Dial-A-Ride services throughout Ann Arbor. Mike Schechtman, director of the Ecology Center, spoke in favor of Teltran at a January 1973 City Council meeting. He described it as a “flexible” plan “which [would] effectively serve ridership demand throughout the entire city,” but warned that the goal of revitalizing downtown Ann Arbor could still be “handicapped… by the excessive demands of peak flow traffic for wider roads and more parking structures.”

On April 2, 1973, both proposals passed by a wide margin. But, as Ann Arbor entered a period of financial hardship and City Council became divided, the proposals’ implementation was delayed. Human Rights Party City Councilman Gerry DeGrieck suggested adding eight members to the AATA board “to ensure representation by diverse segments of the community.” He argued, and the Ecology Center agreed, that the people who used the AATA’s services should have a say in how decisions about them were made. His motion was denied. The AATA assembled an eight-member “citizen advisory board” to provide feedback, but its demographics were not representative of Ann Arbor’s bus-riding population and the Ecology Center questioned whether this board had any influence at all.

In debates over the future of public transportation in Ann Arbor, the Ecology Center fought for citizen input in the policymaking process. Although preventing air and noise pollution, protecting green spaces, and promoting transportation alternatives were their ultimate goals, the staff of the Ecology Center and their allies in neighborhood associations knew these outcomes could not occur unless they forced the city to listen to what they had to say.

The enthusiastic input of concerned citizens made City Council meetings a “weekly spectacle,” according to an article in the Spring 1973 issue of Ann Arbor Scene Magazine. The article’s skeptical author suggested that attendees brush up on the environmentalists’ rhetoric before attending a City Council meeting: “One may never find out what ‘alternatives to the automobile’ are, but one may rest assured that the ‘environmental impact’ of continuing our current automobile oriented planning will be disastrous.” Although outsiders might think their language was dense, the environmentalists believed that all would benefit from the suggestions they offered.

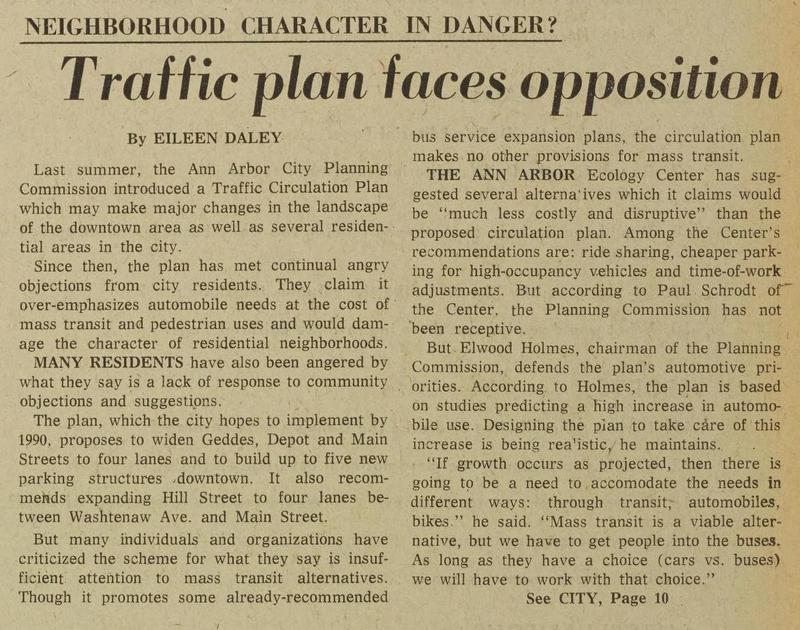

In 1973, City Council created a committee to study traffic problems in Ann Arbor to predict the city’s transportation needs in 1990. Two years later, in March 1975, the committee released a preliminary version of the City Circulation Plan. Ann Arbor Tomorrow, a local business owners’ association, was the only group asked to comment on an early draft. As a result, the Ecology Center’s March 1975 newsletter criticized the plan’s “lack of emphasis on strategies to minimize additional automobile impact throughout Ann Arbor.” The final version, released in September 1976, had the same shortcomings. While Center staff were encouraged that the planners recommended improvements to public transportation and opening more bike paths, they were concerned that the plan’s main solutions to traffic congestion were widening main roads and building parking structures downtown.

The Ann Arbor Planning Commission “got an earful of informed public opinion” on October 5, 1976. Of twenty-seven speakers, twenty-five criticized the plan. Doug Rzepecki of the Sierra Club voiced their main concern: “instead of decreasing demand, this plan increases capacity.” Rather than actively encouraging travelers to use mass transit, bicycles, and their own feet, the plan passively presented those alternatives as options while accommodating the city’s ever-growing automobile population. Furthermore, the speakers were troubled that the plan offered no estimations of environmental impacts or costs to taxpayers. At the end of the meeting, the Commission returned the plan to the committee for revisions; their concerns had been heard.

In the midst of a nationwide economic crisis, downtown business owners hoped parking structures and wider roads would increase customers’ access to their businesses. Without these changes, they worried that customers might choose instead to shop at places in the suburbs with ample parking, like Briarwood Mall. To pacify the grassroots opposition and soothe the business owners’ fears, the Planning Commission adopted a “Circulation Problem Solving Process” in July 1977. Yet the plan “[failed] to provide impetus for changes that would ease reliance on the auto.” Ecology Center staff member Paul Schrodt urged concerned citizens to remain vigilant in the following months. As plans for road construction projects moved forward, the Ecology Center and other citizens’ groups offered critical feedback and alternative plans, but the financial realities of the city meant they needed to compromise.

Reforming the AATA

The AATA was faced with asimilar fiscal crisis. After ending 1977 with a major deficit, it announced severe cut-backs to Dial-A-Ride and other core services. Ecology Center education coordinator Beth Greenberg spoke out against this plan at an AATA board meeting:

“It is not just the elderly and identifiably handicapped who benefit from this type of mass transit… indeed the poor, very young, limited mobility, and female citizens of Ann Arbor are assured access to full participation in the life of the community by virtue of the safety this service provides. To deny these people service would be a serious step backward for our transportation system.”

Director McCargar offered a proposal that would solve the shortfall while retaining the services that these vulnerable groups needed. But the AATA board voted to proceed with the cutbacks.

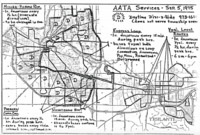

One year later, the AATA offered the public the opportunity to redesign Ann Arbor’s public bus system. Given only ten days to prepare, Center staff wrote up, mapped out, and sent in a plan. Of eight submissions, plans written by the Ecology Center and its ally the Citizens’ Association for Area Planning were selected as two of the final four. The Ecology Center’s plan offered direct bus routes to the city’s center, connected Ann Arbor and Ypsilanti riders to the surrounding communities, and preserved Dial-A-Ride services for the vulnerable groups that used them. Designed around human transportation needs and environmental principles, the Center’s plan would “increase the role of public transportation… and reduce reliance on the automobile.” Following public hearings and performance testing, the AATA board voted to adopt the Ecology Center’s plan.

The Center believed the long-term results of the AATA’s new transit plan would be “cleaner air, lowered energy consumption, less need for road widening and revitalization of two urban centers in our county.” Yet, the plan was another compromise. At the beginning of the decade, the Center had advocated for a radical transformation of Ann Arbor’s transportation system to reduce reliance on private automobiles. But cars continued to dominate Ann Arbor in 1980. The city approved wider, faster roads and issued permits for parking structures where parks used to be. The Ecology Center had called for a shift in cultural attitudes toward transportation, but it seemed the change might not arrive in time.

The Ecology Center could not stop every plan to widen a road or build a parking structure, but it had forced the city to consider how its policies shaped the environment. Without pay, the staff used their expertise to craft proposals which became policy. Many Center staff members brought environmental values with them to their later careers in city government. As a result, in 1980, Ann Arbor had more bike paths, a better bus system, and a team of environmentally-conscious citizens who would continue to fight for a greener future.